Research Article - (2024) Volume 19, Issue 3

*Correspondence: Mohsen Alizadeh Sani, PH.D Associate Professor, Department of Business Administration, Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, University of Mazandaran, Babolsar, Iran,

2PH.D Associate Professor, Department of Business Administration, Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, University of Mazandaran, Babolsar, Iran

3PH.D Associate Professor, Department of Business Administration, Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, University of Mazandaran, Babolsar, Iran

4PH.D Associate Professor, Department of Business Administration, Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, University of Mazandaran, Babolsar, Iran

Received: 10-Jun-2024 Published: 25-Jun-2024

Abstract

Failure to provide services can lead to negative coping behaviors in service recipients, but the perception of the competencies of service providers can reduce such destructive behaviors. Hence, the purpose of this research is to identify the dimensions of required competencies for tourism service providers in religious tourism’s environments in order to prevent the negative behavior of pilgrims (such as revenge and avoidance) in dealing with service failure. This research is a descriptive-exploratory applied research. The statistical population of the study is the religious tourists of Karbala city in the period of July to December 2023, and the research data was collected based on semi-structured in-depth interviews with non-random/ convenient sampling method from 60 religious tourists. The interviews were coded and categorized by thematic analysis method. The findings showed that the following competencies in religious tourism environments -without regarding the order they are placed in- can lead to the reduction of service failure and negative coping behaviors: Practical efficiency; Ability to adapt to the work environment; Adaptability to breakthroughs; Interpersonal skills; Ability to manage time; Problem-solving skills; Reception and etiquette skills; Honesty and privacy in the work environment; Providing help and support.

Keywords

Competencies; Service providers, Religious tourism, Karbala

Introduction

Among the service industries, the tourism industry is one of the leading and growing sectors at the international level (Fourie & Santana-Gallego, 2011) and has been recognized by the United Nations as one of the 10 sectors influencing the green economy (W. T. O , 2013). So that at the global level, the number of domestic and foreign tourists and their income generation is constantly increasing (W.T.O, 2005).

And according to predictions, the demand for international tourism will reach 1.6 billion people per year by 2020 (Coshall et al., 2011). The positive point in the macro planning for the development of the tourism industry is the special attention to the development of human resources in this industry (Khodaee, & kalantari khalilabad, 2013), while many tourism programs for the development of destination areas give little importance to the development of human resources. In addition, many tourism programs support forms of tourism that are not compatible with the capabilities of existing human resources (Liu and Wall, 2006). Since the tourism industry is basically a service activity, therefore, service providers are considered a part of the product, and therefore, the amount of theoretical knowledge and familiarity of people with professional skills is the guarantee of their good performance in order to achieve the goals of this industry. It is clear that with the development of tourism and the more complex needs and expectations of the applicants, the suppliers in this industry must also face this demand, for this purpose the training of the employees is necessary to guarantee the quality of the services and ultimately the satisfaction of the tourists (Edgell et al., 2008).

Examining the factors affecting progress and development in various advanced societies shows that all these countries, in addition to suitable infrastructure and tourism potential, also have capable and efficient educational, professional and educational institutions (Shamsoddini et al., 2015). Neglecting the training of specialized human resources and providing them with the necessary training, as well as neglecting the coordination and matching of the qualitative-quantitative level of human resources with the level of scientific-technical development, or in other words, the empowerment of human resources, creates many problems for the growth and development of the tourism industry. (Hasanpour, 2013). In the service delivery process, there is a possibility of inadequacies, errors, mistakes, and dissatisfactions, and failure in providing services is inevitable, and recovery of such encounters is considered an important challenge for service companies; Because providing inappropriate service quality causes customers to withdraw from service providers. And this means terminating his relationship with the organization and his approach towards other suppliers. As a result, identifying and understanding the cause of customer dissatisfaction with services is a condition for business survival in a competitive situation, one of the reasons of which can be the failure of service quality, which leads to the creation of a negative attitude in customers (Nejati and Rahchamani, 2016).

Religious tourism is the most popular type of tourism in Iraq. Tens of millions of tourists from different countries visit Iraq's religious places every year. Therefore, it is necessary that religious service providers in Iraq have special competencies to satisfy international religious tourists. We have tried to identify and introduce these special competencies in the present research.

Theoretical Foundations of Research

Religious Tourism

Religious tourism is one in which people move from one location to another for religious reasons. Therefore, it understands that religious tourism is considered a sacred market and that it provides a positive well-being for those who visit and for those who are visited. Calvelli (2009) explains Ribeiro (2010) explains that tourism covers trips made for religious reasons, because, regardless of the motivation, travelers use the same equipment, and products and services are generated to meet their expectations. To support the emphasis Silveira (2007) mentions that religious tourism moves pilgrims on journeys through the mysteries of faith or devotion to a saint. In practice, they organize trips to sacred places, events related to evangelization, periodic religious festivals, and religious performances. It is observed that religious tourism is one of the fastest-growing types of tourism, whether due to mystical or dogmatic aspects, as many visitors travel huge distances to meet the sacred.

The notion of religious tourism develops from an understanding of tourist motivations. The difference between this form of tourism and others lies in the religious motivation, which is the reason for the displacement. A criterion related to the destination area can be established, where elements of a religious nature predominate (Ribeiro, 2010).

Jesus (2019) states that John Paul II, in 1986, presented tourism as a bearer of values, thus being a means of responding to the anxieties of the spirit that every human being can obtain when performing this type of displacement. In this understanding, tourism is understood as something greater than simple consumer enjoyment. It also understands that religious tourism is intended to seek spiritual values, which can lead human beings to peace with themselves and especially before God. Silveira (2007, p. 35) confirms that religious tourism related to pilgrimages is associated with the intimate, with the interior of each being, of living a more playful experience of fun, and lightness, among others. In this way, tourism refers to the production of the spectacle in which tourists externalize themselves in a relationship not to know the other, but to establish a better definition of themselves, which also occurs with their past. But religion can also be understood as spectacle, entertainment, vision, and exteriority such as colors and symbols. Therefore, this type of tourism allows an experience with the sacred, which provides a sense of personal well-being.

One of the characteristics of religious tourism is that it allows people to find meaning in existence, for this reason, people travel to centers to raise their religious beliefs and to find themselves at peace with themselves, in other words, it is a mystical exercise in celebration. that every pilgrimage creates and encourages a varied field of religious and interreligious, cultural and intercultural relations, in a comprehensive system of cultural and economic Exchange.

Competence of employees (tourism service providers)

One of the important factors involved in gaining a competitive advantage in the service sector is human resources; Because the employees of the service department interact with their customers to provide services, and it is the quality of this interaction that leads to competitive advantage and differentiation between different organizations. Meanwhile, empowerment has emerged as a well-known tool to increase the ability of employees in organizations, which can guarantee the success of the organization. Despite the general trend of empowerment in service companies, there are still some uncertainties about the impact of empowerment and even about what actually happens (Jafarinia & Darvishon Nejad, 2014). In the tourism industry, it is an unavoidable principle to train specialized and qualified workforce to provide high quality services. Today, with the growing number of tourists, the tourism sector is forced to improve the skills of its employees so that it cannot only meet the expectations of customers, but also exceed them. The researchers state that: the concept of competence includes many different departments and fields of studies and these studies have led to the identification and formation of different approaches and models of competence. There are two main approaches to competencies in the research literature: strategic approach at the organizational level (including tasks, processes and organizational workflows), and the approach of human resources at the individual level (including: basic indicators related to work such as: skills, attitudes, beliefs, motivations and characteristics); These approaches are very closely related to each other (Mohammadi et al., 2017). The current research has examined the approach of human resources at the individual level.

Models of Competency

There are several competency models in the literature. Researchers have divided these models into two main parts: general model and specific organizational model; General models are considered for the complete classification of employees and industries, as well as special organizational models that emphasize the complex needs of an organization. General models can be used as a starting point for the development of a specific organizational model in any type of organization. Among the human resource competency models that exist in the field of tourism, the following can be mentioned:

The competency model by Kim et al. (2011) for hotel employees with dimensions of knowledge, skills, abilities, attitude, and motivation. ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) competency model (2012), for hotel employees with dimensions of general competencies and functional competencies in the form of skills, knowledge, and attitude-behavior. Kamau & Waudo's (2012) competency model, for managers' expectations of employees' competencies including dimensions (basic skills, good attitude, receptive training, interpersonal relationships, creativity, technical skills, and information technology skills), Liaman's competency model (2014), for hotel employees with dimensions of skill, specialization, ability and talent, Shiri and Yousefi's competency model (2013), for managers with managerial, personality, professional, decision-making, team, perceptive, leadership and ethical dimensions. The conceptual model of competence of Dembovska, & Silicka (2015), to provide high-quality services in the hotel industry, includes the dimensions of personal characteristics: knowledge, skills, values, motivations, and enthusiasm. Morteza's competency model (2015), for employees with the dimensions of decision-making skills, social competence, basic knowledge, human relations, professional skills, and leadership skills. and the model of Weinland et al (2016) for leisure managers, including perceptual and creative dimensions, mutual relations, leadership, technical, and executive.

The task of employees who are related to knowledge, skills and attitudes is a worrying situation for the effective and efficient functioning of various organizational functions. In addition, human resources development methods probably strengthen the perception of membership and commitment of employees to the organization, which themselves lead to an increase in their efforts to achieve organizational goals beyond the minimum work requirement. The higher level and quality of in-role and extra-role task efforts determined by the increased competence and commitment of employees causes the effectiveness of organizational performance.

Research Background

Teixeira et al (2021). Investigated the “Religious tourism in municipalities in the state of Amazonas”.

Siti et al. (2011) describe Islamic tourism in Malaysia in their research.

Suleiman and Mohammad (2011) in their article entitled the effect of factors affecting the religious tourism market, a case study of the Palestinian territories, show the importance of religious tourism in Palestine. This article concludes that Palestine is unique due to its history, cultural heritage, geographical location, environment and religions.

Duman (2011) provides an overview of the Halal tourism market in Turkey in his article.

Alizadehsani et al. (2020). Investigate the “Coping behavior of tourists during service failure: the role of perceived competency of human resources”.

After reviewing the literature and emphasizing the importance of service providers' competencies in the religious tourism sector, the research question is:

• What do tourists expect from service providers in a religious tourism environment? In other words, what competencies should service providers in religious tourism environments have?

Methodology

The approach of this study is qualitative because it deals with an in-depth analysis of the research topic, which aims to analyze the main competencies of religious tourism service providers.

In terms of methodological goals, an exploratory and descriptive study has been considered. An exploration to seek a deeper understanding of the subject, which differentiates it to work with the importance of service provider competencies related to religious tourism. Descriptive is to describe the causes of phenomena related to specific goals. The data collection process is to use primary data derived from in-depth semi-structured interviews with religious tourists. The statistical population of the study is the religious tourists of Karbala city in the period of July to December 2023, and non-random/ convenient sampling method from 60 religious tourists. The interviews were coded and categorized by thematic analysis method. To measure validity, Lincoln and Guba (1985) method was used, and to measure reliability of coding, two coder reliability method was used.

Findings

Demographic characteristics of the respondents

In this part, concerning the competencies of religious tourism service providers in Iraq, in-depth semi-structured interviews have been conducted until reaching theoretical saturation. The respondents’ demographic characteristics are presented in the table below (Table 1).

| Nickname | Country | Gender | Age | Marital status | Education |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Iraq - Babylon | Male | more than 50 y | Married | Under Diploma |

| 2 | Iraq - Babylon | Male | 21 - 30 years | single | Master |

| 3 | Iraq - Baghdad | Male | under 20 years | single | Under Diploma |

| 4 | Iraq - Kirkuk | Male | 41 - 50 years | Married | Diploma |

| 5 | Iraq - Baghdad | Female | 31 - 40 years | Single | Diploma |

| 6 | Bahrain | Male | 21 - 30 years | single | Bachelor’s |

| 7 | Bahrain | Female | more than 50 y | Married | Under Diploma |

| 8 | Iraq - Diwaniyah | Female | 31 - 40 years | Married | Bachelor’s |

| 9 | Iraq - Babylon | Female | 41 - 50 years | Married | Bachelor’s |

| 10 | Kuwait | Female | more than 50 y | Married | Bachelor’s |

| 11 | Iran | Male | 21 - 30 years | single | Under Diploma |

| 12 | Iraq -Najaf | Female | 31 - 40 years | single | Bachelor’s |

| 13 | Iraq - Baghdad | Female | more than 50 y | Married | Diploma |

| 14 | Iraq - Baghdad | Male | 41 - 50 years | Married | Diploma |

| 15 | Iraq- Dhi Qar | Male | 21 - 30 years | Married | Diploma |

| 16 | Iraq - Kirkuk | Male | 21 - 30 years | Married | Under Diploma |

| 17 | Iraq - Kirkuk | Male | 31 - 40 years | Married | Bachelor’s |

| 18 | Iraq- Diyala | Male | under 20 years | single | Under Diploma |

| 19 | Iraq -Najaf | Female | 31 - 40 years | single | Master |

| 20 | Iraq - Baghdad | Male | 41 - 50 years | Married | Bachelor’s |

| 21 | Iraq - Baghdad | Male | more than 50 y | Married | Diploma |

| 22 | Iraq - Basra | Female | 21 - 30 years | single | Bachelor’s |

| 23 | Iraq - Basra | Male | 21 - 30 years | single | Bachelor’s |

| 24 | Iraq - Diwaniyah | Female | 21 - 30 years | single | Diploma |

| 25 | Iraq - Babylon | Female | 41 - 50 years | Married | Diploma |

| 26 | Iraq - Baghdad | Female | more than 50 y | Married | Bachelor’s |

| 27 | Iraq - Baghdad | Male | 31 - 40 years | Married | Bachelor’s |

| 28 | Iraq- Diyala | Male | 31 - 40 years | single | Bachelor’s |

| 29 | Iraq- Diyala | Male | 21 - 30 years | single | Diploma |

| 30 | Iraq - Basra | Female | 31 - 40 years | Married | Bachelor’s |

| 31 | Iran | Male | 41 - 50 years | Married | Under Diploma |

| 32 | Iraq - Baghdad | Male | more than 50 y | single | Under Diploma |

| 33 | Iraq- Dhi Qar | Female | 31 - 40 years | Married | Master |

| 34 | Iraq -Najaf | Male | 31 - 40 years | Married | Bachelor’s |

| 35 | Iraq -Najaf | Male | 21 - 30 years | Married | Diploma |

| 36 | Iraq - Basra | Male | 31 - 40 years | single | Bachelor’s |

| 37 | Iraq - Basra | Male | 31 - 40 years | Married | Bachelor’s |

| 38 | Iraq- Dhi Qar | Male | more than 50 y | Married | Bachelor’s |

| 39 | Iraq - Baghdad | Male | more than 50 y | Married | Under Diploma |

| 40 | Iraq -Najaf | Male | 41 - 50 years | Married | Diploma |

| 41 | Iraq - Babylon | Female | 41 - 50 years | single | Diploma |

| 42 | Iraq - Babylon | Female | 41 - 50 years | Married | Diploma |

| 43 | Iraq - Baghdad | Male | 41 - 50 years | Married | Doctorate |

| 44 | Iraq - Diwaniyah | Female | 21 - 30 years | Married | Diploma |

| 45 | Iraq - Basra | Female | 41 - 50 years | Married | Bachelor’s |

| 46 | Iran | Male | 31 - 40 years | Married | Bachelor’s |

| 47 | Iraq - Baghdad | Female | 21 - 30 years | single | Diploma |

| 48 | Iraq- Maysan | Female | 21 - 30 years | Married | Under Diploma |

| 49 | Iraq- Maysan | Female | 41 - 50 years | Married | Under Diploma |

| 50 | Iraq- Dhi Qar | Female | more than 50 y | Married | Under Diploma |

| 51 | Iraq -Najaf | Male | 21 - 30 years | single | Bachelor’s |

| 52 | Iraq -Najaf | Female | 41 - 50 years | Married | Diploma |

| 53 | Iraq - Babylon | Female | 31 - 40 years | single | Doctorate |

| 54 | Iraq - Baghdad | Male | under 20 years | single | Under Diploma |

| 55 | Iraq - Baghdad | Male | 21 - 30 years | Married | Diploma |

| 56 | Iraq- Maysan | Male | 41 - 50 years | Married | Bachelor’s |

| 57 | Iraq - Basra | Female | 31 - 40 years | Married | Master |

| 58 | Iraq -Najaf | Female | 41 - 50 years | Married | Diploma |

| 59 | Iraq - Baghdad | Female | 21 - 30 years | single | Bachelor’s |

| 60 | Iraq - Basra | Female | 31 - 40 years | single | Bachelor’s |

Analyzing the data: Thematic Analysis (TA)

TA is a method for systematically identifying, organizing, and offering insight into, patterns of meaning (themes) across a dataset. Through focusing on meaning across a dataset, TA allows the researcher to see and make sense of collective or shared meanings and experiences. Identifying unique and idiosyncratic meanings and experiences found only within a single data item is not the focus of TA. This method, then, is a way of identifying what is common to the way a topic is talked or written about, and of making sense of those commonalities.

However, what is common is not necessarily in and of itself meaningful or important. The patterns of meaning that TA allows the researcher to identify need to be important in relation to the particular topic and research question being explored. Analysis produces the answer to a question, even if, as in some qualitative research, the specific question that is being answered only becomes apparent through the analysis. There are numerous patterns that could be identified across any dataset - the purpose of analysis is to identify those relevant to answering a particular research question. For instance, in researching white collar workers’ experiences of sociality at work, a researcher might interview people about their work environment, and start with questions about their typical work day. If most or all reported that they started work at around 9am, this would be a pattern in the data, but it wouldn’t necessarily be a meaningful or important one. However, if many reported that they aimed to arrive at work earlier than they needed to, to chat to colleagues, this could be a meaningful pattern.

Thematic analysis is a flexible method that allows the researcher to focus on the data in numerous different ways. With TA you can legitimately focus on analyzing meaning across the entire dataset, or you can examine one particular aspect of a phenomenon in depth. You can report the obvious or semantic meanings in the data, or you can interrogate the latent meanings, the assumptions and ideas that lie behind what is explicitly stated (see Braun & Clarke, 2006). The many forms thematic analysis can take means that it suits a wide variety of research questions and research topics.

4-3-1-1-Coding the phrases extracted from the interviews

Generally, thematic analysis has two stages including open and axial coding. In the open coding phase, the label / concept or open code is assigned to the phrase which is related to the research question, and the axial coding is to compare and find similarities among the open codes and classify them into a group under the title of category. Both stages are done in the table below Table 2.

Employee Competencies |

|

|---|---|

| Dimension | Indicator |

| Dimension 1: Practical efficiency |

Being efficient and organized |

| Experienced in providing services | |

| Having a certificate and education related to the nature of their work | |

| Keeping up with progress and technology | |

| Teamwork oriented | |

| Flexible in performing work | |

| Dimension 2: Ability to adapt to the work environment |

Understanding the visitors' needs |

| Good behavior and tact | |

| Effective communication skills | |

| Adherence to politeness, proper appearance, and wearing the specified uniform | |

| Observance of personal hygiene | |

| Compatibility with the nature and work environment | |

| Dimension 3: Adaptability to breakthroughs |

ability to make appropriate decisions |

| Adaptability to quick and sudden changes | |

| Patience and ability to deal with and make decisions | |

| Ability to withstand difficult conditions | |

| Dimension 4: Interpersonal skills |

Humane dealing and honesty in doing business |

| Tolerate criticism | |

| Respectful, calm and decent interaction with visitors | |

| The ability to persuade and professionalism in performing work | |

| Dimension 5: Ability to manage time |

Ability to work overtime |

| Respecting the pilgrims' time | |

| Time management | |

| Completing work within the specified times | |

| Adherence to official working hours | |

| Dimension 6: Problem-solving skills |

The ability to identify a problem and then solve it |

| Ability to deal with unexpected challenges such as flight delays or emergencies | |

| The ability to deal with challenges rationally | |

| Helping visitors find their loved ones (children, for example) and lost items in crowds | |

| Trying to solve problems and provide support as soon as possible | |

| The ability to think creatively and find innovative solutions to problems | |

| Dimension 7: Reception and etiquette skills |

Organizing the arrival and departure of visitors |

| Having good manners and hospitality | |

| Proficiency in other languages | |

| Accepting different nationalities with warmth and interest | |

| Knowledge of Sharia rulings related to worship and religious rituals | |

|

Dimension 8: Honesty and privacy in the work environment |

Honesty in performing job duties |

| Protection of confidential and personal information | |

| Adherence to privacy and security policies | |

| Knowledge of security procedures | |

| Check the authenticity of the documents | |

| Storage of visitors' luggage | |

| Applying the security procedures properly | |

| Compliance with rules and regulations | |

| Providing reliable and factual information | |

|

Dimension 9: Providing help and support |

Answer phone calls at all times |

| Providing support and assistance to people with special needs (such as the elderly and disabled) and understanding their needs | |

| Assisting in a cooperative spirit | |

During the interviews, concepts were extracted from the interviews and placed in their respective categories. This process progressed until the extraction of concepts was met with theoretical saturation and no new concepts were extracted (Table 2).

Competencies dimensions of service providers in Religious Tourism

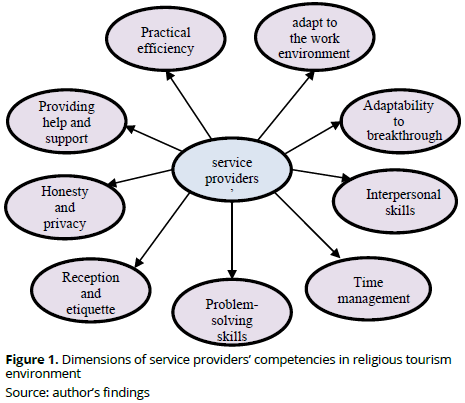

Figure 1, shows dimensions of service providers’ competencies in religious tourism environment without regard for the order they are placed in. as you see there are 9 dimensions including:

Source: author’s findings

Dimension 1: Practical efficiency; Dimension 2: Ability to adapt to the work environment; Dimension 3: Adaptability to breakthroughs; Dimension 4: Interpersonal skills; Dimension 5: Ability to manage time; Dimension 6: Problem-solving skills; Dimension 7: Reception and etiquette skills; Dimension 8: Honesty and privacy in the work environment; Dimension 9: Providing help and support (Figure 1).

Discussion and Conclusion

Failure to provide services can lead to negative coping behaviors in service recipients, but the perception of the competencies of service providers can reduce such destructive behaviors. Hence, the purpose of this research is to identify the dimensions of required competencies for tourism service providers in religious tourism environments to prevent the negative behavior of pilgrims (such as revenge and avoidance) in dealing with service failure.

Religious tourism is the most popular type of tourism in Iraq. Tens of millions of tourists from different countries visit Iraq's religious places every year. Therefore, religious service providers in Iraq must have special competencies to satisfy international religious tourists. We have tried to identify and introduce these special competencies in the present research. after interviewing 60 pilgrims in Karbala, the following service providers' competencies have been extracted -without regarding the order they are placed in - that can lead to the reduction of service failure and negative coping behaviors: Practical efficiency; Ability to adapt to the work environment; Adaptability to breakthroughs; Interpersonal skills; Ability to manage time; Problem-solving skills; Reception and etiquette skills; Honesty and privacy in the work environment; Providing help and support.

Kim et al. (2011) designed a questionnaire to measure the competence of employees, which has three dimensions: ability (17 items), knowledge (8 items) and skill (12 items). Compared to the work of Kim et al., the present study has 9 dimensions, in addition to covering the above three dimensions, it has a special emphasis on welcoming skills, etiquette, honesty, and privacy in the workplace. Also, the results of the present study are in line with Alizadeh et al.'s (2020) research in terms of the importance of the competence of tourism service providers in recreational tourism environments, with the difference that the present study deals with the dimensions of competence in the religious tourism environment.

as mentioned in the theoretical foundation there are several competency models which are in the field of organization and hospitality including:

The competency model by Kim et al. (2011) for hotel employees with dimensions of knowledge, skills, abilities, attitude, and motivation. ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) competency model (2012), for hotel employees with dimensions of general competencies and functional competencies in the form of skills, knowledge, and attitude-behavior. Kamau & Waudo's (2012) competency model, for managers' expectations of employees' competencies including dimensions (basic skills, good attitude, receptive training, interpersonal relationships, creativity, technical skills, and information technology skills), Liaman's competency model (2014), for hotel employees with dimensions of skill, specialization, ability and talent, Shiri and Yousefi's competency model (2013), for managers with managerial, personality, professional, decision-making, team, perceptive, leadership and ethical dimensions. The conceptual model of competence of Dembovska, & Silicka (2015), to provide high-quality services in the hotel industry, includes the dimensions of personal characteristics: knowledge, skills, values, motivations, and enthusiasm. Morteza's competency model (2015), for employees with the dimensions of decision-making skills, social competence, basic knowledge, human relations, professional skills, and leadership skills. and the model of Weinland et al (2016) for leisure managers, including perceptual and creative dimensions, mutual relations, leadership, technical, and executive.

the context of abovementioned competency models demonstrates that a very few researches present a competency model, pattern or framework in the context of religious tourism environments. hence the findings of this research can be useful and practical for such demanding places.

References

Alizadehsani., M., Anvari, F., & Jamali, F. (2020). Coping behavior of tourists during service failure: the role of perceived competency of human resources. Journal of Tourism Planning and Development, 8(31), 133-146. doi: 10.22080/jtpd.2020.17592.3165

Association of SouthEast Asian Nations (ASEAN), (2012). Guide to ASEAN Mutual Recognition Arrangement on Tourism Professionals: http://www.asean.org/storage/images/%20Hospitality.pdf

Calvelli, H. G. (2009), “Turismo religioso no caminho da fé”. Revista eletrônica de Turismo Cultural. ISSN 1981-5646. V.3. N.01, disponível em: http://eca.usp.br/turismocultural/05_Caminho_da_f%C3%A9-Haudrey.pdf (acessado em 11 nov. 2020).

Coshall, J. T., & Charlesworth, R. (2011). A management orientated approach to combination forecasting of tourism demand. Tourism Management, 32(4), 759-769.

Dembovska, I., & Silicka, I. (2015). Competences that Shape Service Quality at Hospitality Enterprises, Innovative (Eco-) Technology, Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, Conference proceedings.

Duman, T. (2011), Value of Islamic Tourism Offering: Perspectives from the Turkish Experience, World Islamic Tourism Forum, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Edgell, D., & Allen, M., & Smith, G., & Swanson, J. (2008). Tourism policy and planning. London.

Fourie, J., & Santana-Gallego, M. (2011). The impact of mega-sport events on tourist arrivals. Tourism management, 32 (6), 1364-1370.

Jafarinia, S., & Darvishon Nejad, R. (2014). Investigating the Impact of Employee Empowerment on Service Quality and Customer Loyalty with an Emphasis on the Mediating Role of Customer Satisfaction in the Banking Industry. Public Organizations Management, 2(2), 51-65.

Jesus, E. T. de. (2019), “O turismo e a busca de sentido: a hospitalidade nos bastidores das peregrinações católicas”. 179f. Tese (Doutorado em Turismo e Hotelaria) – Universidade de Caxias do Sul – UCS, Caxias do Sul, RS: UCS, 2019.

Kamau, S. W., & Waudo, J. W. (2012). Hospitality industry employer’s expectation of employees’ competences in Nairobi Hotels, Journal of Hospitality Management and Tourism, 3 (4), 55-63

Khodaee, z., & kalantari khalil abad, h. (2013). Tourism development with emphasis on the role of workforce training. Urban management studies, 4(12), 47-59. Sid. Https://sid.ir/paper/199339/en.

Kim, Y., Kim, S. S., Seo, J. and Hyun, J. (2011). Hotel Employees' Competencies and Qualifications Required According to Hotel Divisions, Journal of Tourism, Hospitality & Culinary Arts, 3 (2), 1-18.

Liaman, A. (2014). Competencies and Qualifications of Staff and Management in Hospitality Establishments, Bachelor dissertation, Institute of Hospitality Management in Prague.Lin, W. B. (2010). Service failure and consumer switching behaviors: Evidence from the insurance industry. Expert Systems with Applications, 37: 3209-3218.

Lincoln, Y. S., & E. G. Guba, (1985). Naturalistic inquiry, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Liu, A., & Wall, G. (2006). Planning tourism employment: a developing country perspective. Tourism Management, 27 (1), 159-170.

Mohammadi, M., Mirtaghian Rudsari, S. M., & Salehi, S. (2017). Individual Competencies of Human Resources and Loyalty Intentions of Guests in the Four Stars Hotels of Mazandaran Province. Tourism Management Studies, 11(35), 63-84. doi: 10.22054/tms.2017.7080.

Murtaza, Z. (2015). Competency Mapping in Hotels with Reference to Kashmir, Journal of Exclusive Management Science, 4 (3), 1-13.

Nejati, N., Rahchamani, A. (2016). Effect of failed service quality on customer loyalty in banking industry, Journal of Marketing Management, 11(30), 93-109. magiran.com/p1921316.

Ribeiro, C. M. (2010), “Turismo religioso: fé, consumo e mercado”. Revista Facitec. ISSN 19881 – 3511. V.5. n.1. Art.06, Ago – Dez, 2010, disponível em: https://docplayer.com.br/19055000-Turismo-religioso-fe-consumo-e-mercado.html (acessado em 8 nov. 2020).

Shamsoddini, A., Derakhshan, E., and Karimi, B (2017). The effect of empowerment of human resources in tourism development Case Study: Kohgiluyeh & Boyer-Ahmad province, Journal of Regional Planning, 6(24), 89-100.

Silveira, E. J. S. da. (2007), “Turismo Religioso no Brasil: Uma perspectiva local e global”. Turismo em Análise, Balneário Camboriú, v. 18, n. 1, p. 33-51, disponível em:DOI : 10.11606/issn.1984-4867.v18i1p33-51.

Siti, Anis Laderlah, Suhaimi Ab Rahman, and Khairil Awang, (2011), a Study on Islamic Tourism: A Malaysian Experience, 2nd International Conference on Humanities, Historical and Social Sciences, Singapore.

Suleiman, Jafar Subhi Hardan & Mohamed, Badaruddin, (2011), Factors Impact on Religious Tourism Market: The Case of the Palestinian Territories, International Journal of Business and Management Vol. 6, No 7.

Teixeira, M. A., Barbosa Santos, L. C., Ramos Iwata, M. J., & Peixoto de Oliveira, A. G. (2021). Religious tourism in municipalities in the state of Amazonas. Via. Tourism Review, (20).

Weinland, J. T., Gregory, A. M., & Petrick, J. A. (2016). Cultivating the aptitudes of vacation ownership management: A competency domain cluster analysis, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 55,88-95.

World Tourism Organization (2005). Tourism Highlights 2006 editions.

World Tourism Organization, (2013),"Sustainable Tourism for Development" Guidebook.