Research Article - (2024) Volume 19, Issue 6

Hepatitis B Awareness Among An Adult Population At Northern Saudi Arabia

Mohamed M Abd El Mawgod1,2*, Prof. Shereen Mohamed Olma3, Nasser Obaylik M Alruwaili4, Bader Muhammad G AlRwaili4, Khalil Yousef N Alruwaili4 and Faris Yousef N Alruwaili4*Correspondence: Mohamed M Abd El Mawgod, Department of Family and Community Medicine, College of Medicine, Northern Border University, Arar, Saudi Arabia, Email:

2Department of Public Health and Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Al Azhar University, Assiut, Egypt

3Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, Northern Border University, Arar, Saudi Arabia

4Medical Student, College of Medicine, Northern Border University, Arar, Saudi Arabia

Received: 06-Dec-2024 Published: 15-Dec-2024

Abstract

Introduction

HBV infection is still a major concern for global public health. According to WHO 1.5 million new cases of infection were found in 2019, leaving 296 million people with the disease(WHO, 2022). Compared to Western countries, where it affects less than 1% of the population, the Middle Eastern region has a higher prevalence of HBV infection (Habibzadeh, 2014). The prevalence of HBV is presently 1.7% in Saudi Arabia, according to the latest statistics and modeling research (Abaalkhail et al., 2021, Sanai et al., 2020).

Researchers from all across the world conducted research into public and/or healthcare practitioner knowledge, attitudes, and practices about HBV. More awareness of the disease and sufficient comprehension were linked to higher vaccination rates (Gürakar et al., 2014). A low degree of awareness regarding the illness, particularly the methods of HBV transmission, was identified by Hislop, et al. (Hislop et al., 2007). The usage of the internet and the media for health information on the disease, as well as being younger, having more education, and knowing more about HBV were all found to be significant predictors of knowledge (Yau et al., 2016). The general population ignores or is not aware of hepatitis B screening and infection-prevention vaccinations (Ma et al., 2007). The general population also knows little about the complications of HBV (Thompson et al., 2002).

HBV can be spread through sexual contact, the use of contaminated syringes, needles, or other injectable supplies, or even from mother to baby at birth (CDC, 2017). Higher levels of HBV are present in blood and serous exudates. For patients with characteristics, such as hepatic illness that is uncompensated, and immunosuppression, an interferon-alpha (IFN-alpha) has limited success in the treatment of persistent HBV infections (Subaiea et al., 2017). Additionally, ribavirin (Wang et al., 2017), which has broad-spectrum antiviral activity, was one of many medicines that were tried and failed as prospective anti-HBV treatments(Aljofan et al., 2010). Chronic HBV infection is still incurable at this time (Aljofan et al., 2014).

HBV infection is a serious issue that affects people all over the world. It causes chronic liver disease and can even result in liver cirrhosis or liver cancer, which can be fatal. The study aimed to explore the awareness of HBV infection among the adult public in Arar City, Northern Saudi Arabia.

Subjects and methods

Study setting and design: A cross-sectional study was conducted among the adult public aged 18 years and older at Arar City (The capital of the Northern Border Province), Kingdom of Saudi Arabia between December 1, 2023, and October 31, 2024.

Study tools

A structured questionnaire was constructed by reviewing the previous relevant studies. The questionnaire included 3 parts:

- The 1st part included socio-demographics as age, gender, marital status, and educational level

- General concepts on the symptoms and signs of hepatitis B as well as its modes of transmission of hepatitis B were covered in the second part.

- Questions about prevention, treatment choices, and social stigma among affected individuals were included in the 3rd part.

Sampling method

Using an online questionnaire approach with an Arabic version and social media platforms like Telegram groups and WhatsApp, the data were gathered from the participants. Informed consent was present at the beginning of the questionnaire including the study objective to be read and approved by the participants.

Sample size

Using Epi info software program for sample size calculations version 7.2.4.0, taking 50% expected level of awareness, 0.05 margin of error, and confidence level 95% the estimated sample size according to the mentioned inputs is 384. Four incomplete questionnaires were received and excluded leaving 380 for analysis, with a response rate of around 99%.

Statistical analysis

The data was collected and then analyzed using SPSS version 16. Categorical data are presented as frequency and percentage, whereas numerical data are presented as mean ±SD.

Inclusion criteria: Participants who are above 18 years old and accepted participation in the study

Exclusion criteria: Individuals under the age of eighteen and people declined to take part in the research.

Ethical consideration: The research was approved by the local bioethical committee at the Northern Border University (HAD-09-A-043) with decision no. (2-24-H) dated 16-01-2024.

Results

Table (1) displays various demographic parameters of the participants. A total of 380 participants were included, the majority of them from the Northern Border Region (86.1%), with a mean age of 31.6 ±10.1years, almost 55% of them are under 30 years old, females make up slightly more than half (52.1%), fifty percent unmarried, and more than two-thirds university have a university degree (75.3%). These match broader societal trends with younger generations.

| Item | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean ± SD= 21.8±1.5 | |

| Sex | Male | 108(43.2) |

| Female | 142(56.8) | |

| Academic level | 2nd year | 47(18.8) |

| 3rd year | 51(20.4) | |

| 4th year | 50(20) | |

| 5th year | 48(19.2) | |

| 6th year | 54(21.6) | |

| Marital status | Single | 246(98.4) |

| Married | 4(1.6) | |

| *GPA | 2.5-2.99 | 7(2.9) |

| 3-3.49 | 9(3.6) | |

| 3.50-3.99 | 33(13.2) | |

| 4-4.49 | 92(36.8) | |

| 4.5 and above | 109(43.5) | |

| Smoking habits | Smoker | 25(10) |

| Ex-smoker | 9(3.6) | |

| Non-smoker | 216(86.4) | |

| Mother education | Uneducated | 27(10.8) |

| Primary | 18(7.2) | |

| Intermediate | 45(18) | |

| Secondary | 160(64) | |

| Mother job | Housewife | 109(43.6) |

| Governmental | 118(47.2) | |

| Private | 9(3.6) | |

| Other | 14(5.6) | |

| Father education | Uneducated | 18(7.2) |

| Primary | 16(6.4) | |

| Intermediate | 60(24) | |

| Secondary | 156(62.4) | |

| Father job | Unemployed | 6 (2.4) |

| Governmental | 131(52.4) | |

| Private | 11(4.4) | |

| Other (Freelancer) | 102(40.8) | |

| Family income | Unsatisfactory | 69(27.6) |

| Enough | 168(67.2) | |

| More than enough | 13(5.2) |

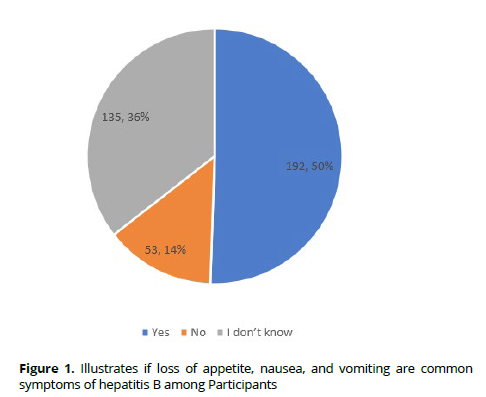

As shown in Figure 1, Insightful perspectives about the symptoms of hepatitis B among respondents are presented. Nearly half of the participants (192, 50.53%) agreed that loss of appetite, nausea, and vomiting were common symptoms of hepatitis B; indicating that there is widespread familiarity with these clinical symptoms within the population. About one-third (135, 35.5%) were not sure of the symptoms, and a small percentage claimed not to recognize these symptoms (53.13.9%), an area that might need further education.

Table 2 shows that the surveyed people were very much aware of the various risk factors and modes of transmission of HBV, but important areas still need attention. A robust majority, almost 73.4 percent, correctly recognized hepatitis B as a viral disease, and only 36.8 percent comprehended its ease of transmission, suggesting there may be a gap in how well people understood it to be contagious. In addition, 68.4 percent cited that any age could be affected and know some general knowledge; however, they lacked the correct recognition of transmission by contaminated food and water, and they were not aware of the similarities with the symptoms of common colds which can all hinder prevention efforts. But while that’s a good more than two-thirds (75.8%) correctly recognized the risks of using unsterilized medical equipment in disease transmission. Health is crying for more emphasis on educating not only the population about the risk of transmission by personal items and sexual contact but that too has turned out to be only 50.5 percent.

| Stressors | Never No (%) |

Almost never No (%) |

Sometimes No (%) |

Often No (%) |

Very often No (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic stressors | |||||

| Frequency of examination | 11(4.4) | 15(6) | 63(25.2) | 93(37.2) | 68(27.2) |

| Performance in Exams | 18 (7.2) | 19(7.6) | 73(29.1) | 79(31.6) | 61(24.4) |

| Academic Curriculum | 16(6.4) | 24(9.6) | 82(32.8) | 75(30) | 53(21.2) |

| Dissatisfaction with class lectures | 18(7.2) | 27(10.8) | 92(36.8) | 73(29.2) | 40(16) |

| Lack of time for recreation | 28(11.2) | 28(11.2) | 81(32.4) | 60(24) | 53(21.2) |

| Fear of becoming a physician | 34(13.6) | 35(14) | 72(28.8) | 55(22) | 54(21.6) |

| Competition with Peers | 44(17.6) | 39(15.6) | 78(31.2) | 51(20.4) | 38(15.2) |

| Lack of special guidance from the college | 41(16.4) | 48(19.2) | 76(30.4) | 44(17.6) | 41(16.4) |

| Inadequate learning materials | 37(14.8) | 52(20.8) | 85(34) | 46(18.4) | 30(12) |

| Performance in practical | 60(24) | 46(18.4) | 75(30) | 44(17.6) | 25(10) |

| Psychosocial stressors | |||||

| Political situation in the world | 36(14.4) | 27(10.8) | 69(27.6) | 55(22) | 63(25.2) |

| High Parental Expectations | 32(12.8) | 44(17.6) | 74(29.6) | 63(25.2) | 37(14.8) |

| Loneliness | 35(14) | 36(14.4) | 81(32.4) | 70(28) | 28(11.2) |

| Lack of entertainment in the institution and the city | 44(17.6) | 40(16) | 79(31.6) | 45(18) | 42(16.8) |

| interaction with the other gender | 45(18) | 54(21.6) | 87(34.8) | 49(19.6) | 15(6) |

| Family Problems | 77(30.8) | 49(19.6) | 64(25.6) | 45(18) | 15(6) |

| Financial strain | 83(33.2) | 41(16.4) | 71(28.4) | 34(13.6) | 21(8.4) |

| Difficulty in reading textbooks | 72(28.8) | 51(20.4) | 75(30) | 37(14.8) | 15(6) |

| Inability to communicate with peers | 85(34) | 43(17.2) | 76(30.4) | 32(12.8) | 14(5.6) |

| Accommodation away from home | 150(60) | 23(9.2) | 41(16.4) | 26(10.4) | 10(4) |

| Living conditions in the hostel | 157(62.8) | 22(8.8) | 41(16.4) | 20(8) | 10(4) |

| Lack of personal interest in medicine | 138(55.2) | 28(11.2) | 55(22) | 18(7.2) | 11(4.4) |

| Worrying about the future | 145(58) | 40(16) | 39(15.6) | 19(7.6) | 7(2.8) |

| Difficulty in the journey back home | 123(49.2) | 47(18.8) | 53(21.2) | 18(7.2) | 9(3.6) |

| Being a member of a student association | 156(62.4) | 27(10.8) | 41(16.4) | 20(8) | 6(2.4) |

| Adjustment with roommate/s | 161(64.3) | 26(10.4) | 39(15.5) | 17(6.8) | 7(2.8) |

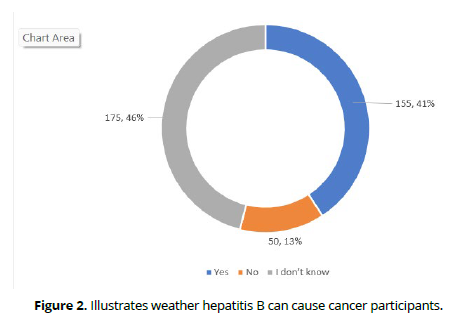

As shown in Figure (2), Results obtained from the data presented offer some significant insights regarding the public awareness of Hepatitis B to liver cancer and the total sample size used is 380. Notably, 155 out of the sample (response rate of 40.8%) affirmatively recognized that Hepatitis B is indeed a cause of liver cancer. However, 50 respondents (13.2%) stated either a lack of awareness or understanding regarding this association with the response "No." A large proportion, comprised of 175 respondents, or 46.1 percent of the total, expressed doubt with "I don't know."

Table 3 shows some of the major things that the participants knew about hepatitis B preventive measures and its complications because they are presented in the data. The remarkable point is that a lot of, 68.7 percent (n = 261), know the fact that hepatitis B has a vaccine, and this is of a positive understanding of preventative methods. But the fact that 30.8 percent (n = 117) do not believe that the body heals itself from hepatitis B illustrates a complicated idea of the virus and what to do about it alongside that high rate (40 percent of 152) who don’t know. At the same time, we find that the data also reflects a serious lack of knowledge about the severe consequences associated with hepatitis B, with only 40.8% (n=155) of respondents aware that it could cause liver cancer. Finally, socio-cultural factors are argued through the responses regarding stigma and comfort when interacting with infected people.

| Health-related stressor | Never No (%) |

Rarely No (%) |

Sometimes No (%) |

Often No (%) |

Very often No (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleeping Difficulties | 22(8.8) | 24(9.6) | 78(31.2) | 79(31.6) | 47(18.8) |

| Nutrition | 29(11.6) | 48(19.2) | 73(29.2) | 67(26.8) | 33(13.2) |

| Class Attendance | 28(11.2) | 43(17.2) | 97(38.8) | 55(22) | 27(10.8) |

| Physical exercise | 54(21.6) | 44(17.6) | 76(30.4) | 52(20.8) | 24(9.6) |

| Food quality in the university restaurant | 97(38.8) | 35(14) | 64(25.6) | 29(11.6) | 25(10) |

| Smoking | 175(70) | 14(5.6) | 44(17.6) | 13(5.2) | 4(1.6) |

| Physical disabilities | 181(72.4) | 14(5.6) | 37(14.8) | 13(5.2) | 5(2) |

Discussion

HBV is a serious infection that can cause both acute and chronic hepatitis, as well as cirrhosis and hepatocellular cancer over time. it can be transmitted both via percutaneous and mucosal routes of exposure to infected blood and any infected body fluids. The virus can also be transferred from mother to kid during childbirth.(Korsman et al., 2012). In 2019, the WHO projected that 96 million people worldwide had a chronic HBV infection and that consequences from cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma caused 820,000 deaths worldwide. (WHO, 2022)

Our study findings on hepatitis B-awareness among adults in northern Saudi Arabia are consistent with and divergent from several previous studies in different populations indicating the pressing need for increased education on hepatitis B transmission, prevention, and complications. Kheir et al (Kheir et al., 2022). also reported that several participants were unvaccinated for hepatitis B, pointing to a public health problem in a high-risk population. Our study further supports this by revealing 68.7% awareness of the hepatitis B vaccine, alongside the 75% who thought they could catch hepatitis B through casual contact, such as hauling hands. We also found similar misconceptions as a large section of respondents did not know that hepatitis B could be transmitted through personal items and sexual contact (50.5%, and 40% respectively). Furthermore, Pui Wah Chung et al (Chung PuiWah et al., 2012), found that only 14% of respondents had good knowledge of hepatitis B, whilst 26% were vaccinated compared to the 73.4% of our cohort who were able to identify hepatitis B as a viral disease. In other words, although the awareness of hepatitis B as a public health threat is widespread, awareness of the transmission routes is low. Our findings are consistent with the studies of Aslam et al. among medical students (Ghouri et al., 2015), which revealed a lack of knowledge about the transmission of hepatitis B transmission via food and water, and highlighted that having such a lack of understanding about the transmission mechanisms increases the risk of spread. Additionally, a study on Syrian medical students (Ibrahim and Idris, 2014) described that although many could recognize the clinical signs of jaundice, their knowledge of the asymptomatic nature of hepatitis B and the severity of its complications was appalling. We confirmed these findings, with only 40.8 percent of participants guessing that hepatitis B could also cause liver cancer, underscoring a big gap in knowing what it is and how severe its health struggles. Furthermore, Mohan B Sannathimmappa et al.'s work (Sannathimmappa et al., 2019). indicated that while 84.8% were aware of hepatitis B, only 28.8% recognized sexual transmission as a mode of spread. This reflects a broader trend echoed in our study, where understanding of various transmission routes remained suboptimal. In contrast, healthcare workers in India demonstrated a high level of awareness, with 100% recognizing blood and blood products as modes of transmission(Setia et al., 2013), suggesting that occupation may play a crucial role in knowledge acquisition. Furthermore, Elegbede et al (Elegbede et al., 2022). reported that only 26% received at least one dose of the hepatitis B vaccine, aligning with our findings on the need for increased vaccination efforts in similar demographic groups. Internationally, studies have shown diminished vaccination rates among adolescents in the US, reinforcing the importance of targeted educational interventions to combat hepatitis B (Le et al., 2020). Comparatively, our study highlights not only knowledge gaps but also stigma associated with hepatitis B that may hinder education and outreach efforts. Additionally, the association between educational level and health knowledge has been corroborated in various studies, including those conducted in Jordan and among Malaysian populations, wherein higher educational attainment correlated with better knowledge of hepatitis B(Robert, 1998, Rajamoorthy et al., 2019).

Conclusion

Finally, our study reveals significant gaps in adult population awareness about hepatitis B in Arar City, Northern Saudi Arabia. Although most participants were aware hepatitis B was a viral disease and knew several risk factors for its transmission, misconceptions about how the disease was transmitted, and the severe complications associated with having hepatitis B, were common. The key finding, though, was that only 36.8% of respondents realized that hepatitis B is contagious and the fact that awareness of hepatitis B's ability to cause liver cancer was alarmingly low at 40.8%. Additionally, although a large proportion (68.7 percent) admit to the existence of a vaccine, uptake is still a serious concern. These findings emphasize the crucial need for broader, more comprehensive work done to educate not only the general public but also in the healthcare provider community to increase public understanding of hepatitis B transmission, prevention, and therapy. The reduction of the burden of hepatitis B and increasing public health outcomes in the region depend on addressing these knowledge gaps.

References

ABAALKHAIL, F. A., AL-HAMOUDI, W. K., KHATHLAN, A., ALGHAMDI, S., ALGHAMDI, M., ALQAHTANI, S. A. & SANAI, F. M. 2021. SASLT practice guidelines for the management of Hepatitis B virus - An update. Saudi J Gastroenterol, 27, 115-126.

ALJOFAN, M., LO, M. K., ROTA, P. A., MICHALSKI, W. P. & MUNGALL, B. A. 2010. Off label antiviral therapeutics for henipaviruses: new light through old windows. Journal of antivirals & antiretrovirals, 2.

ALJOFAN, M., NETTER, H. J., ALJARBOU, A. N., HADDA, T. B., ORHAN, I. E., SENER, B. & MUNGALL, B. A. 2014. Anti-hepatitis B activity of isoquinoline alkaloids of plant origin. Arch Virol, 159, 1119-28.

CDC. 2017. (Center for Disease Prevention and Control) [Online]. Available: http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hbv/index.htm [Accessed].

CHUNG PUIWAH, C. P., SUEN SIKHUNG, S. S., CHAN OIKA, C. O., LAO TZUHSI, L. T. & LEUNG TAKYEUNG, L. T. 2012. Awareness and knowledge of hepatitis B infection and prevention and the use of hepatitis B vaccination in the Hong Kong adult Chinese population.

ELEGBEDE, O. E., ALABI, A. K., ALAO, T. A. & SANNI, T. A. 2022. Knowledge and associated factors for the uptake of hepatitis B vaccine among nonmedical undergraduate students in a private university in Ekiti State, Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Medicine, 31, 401-405.

GHOURI, A., ASLAM, S., IQBAL, Y. & SHAH, A. A. 2015. Knowledge and awareness of hepatitis B among students of a public sector university. Isra Med J, 7, 95-100.

GÜRAKAR, M., MALIK, M., KESKIN, O. & İDILMAN, R. 2014. Public awareness of hepatitis B infection in Turkey as a model of universal effectiveness in health care policy. Turk J Gastroenterol, 25, 304-8.

HABIBZADEH, F. 2014. Viral hepatitis in the Middle East. Lancet, 384, 1-2.

HISLOP, T. G., TEH, C., LOW, A., LI, L., TU, S. P., YASUI, Y. & TAYLOR, V. M. 2007. Hepatitis B knowledge, testing and vaccination levels in Chinese immigrants to British Columbia, Canada. Can J Public Health, 98, 125-9.

IBRAHIM, N. & IDRIS, A. 2014. Hepatitis B awareness among medical students and their vaccination status at Syrian Private University. Hepatitis research and treatment, 2014, 131920.

KHEIR, O. O., FREELAND, C., ABDO, A. E., YOUSIF, M. E. M., ALTAYEB, E. O. & MEKONNEN, H. D. 2022. Assessment of hepatitis B knowledge and awareness among the Sudanese population in Khartoum State. Pan Afr Med J, 41, 217.

KORSMAN, S., VAN ZYL, G., NUTT, L., ANDERSSON, M., PREISER, W., KORSMAN, S., VAN ZYL, G., NUTT, L., ANDERSSON, M. & PREISER, W. 2012. Hepadnaviruses. Virology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 70-71.

LE, M. H., YEO, Y. H., SO, S., GANE, E., CHEUNG, R. C. & NGUYEN, M. H. 2020. Prevalence of Hepatitis B Vaccination Coverage and Serologic Evidence of Immunity Among US-Born Children and Adolescents From 1999 to 2016. JAMA Netw Open, 3, e2022388.

MA, G. X., SHIVE, S. E., FANG, C. Y., FENG, Z., PARAMESWARAN, L., PHAM, A. & KHANH, C. 2007. Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of hepatitis B screening and vaccination and liver cancer risks among Vietnamese Americans. J Health Care Poor Underserved, 18, 62-73.

RAJAMOORTHY, Y., TAIB, N. M., MUNUSAMY, S., ANWAR, S., WAGNER, A. L., MUDATSIR, M., MULLER, R., KUCH, U., GRONEBERG, D. A., HARAPAN, H. & KHIN, A. A. 2019. Knowledge and awareness of hepatitis B among households in Malaysia: a community-based cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health, 19, 47.

ROBERT, S. A. 1998. Community-level socioeconomic status effects on adult health. J Health Soc Behav, 39, 18-37.

SANAI, F. M., ALGHAMDI, M., DUGAN, E., ALALWAN, A., AL-HAMOUDI, W., ABAALKHAIL, F., ALMASRI, N., RAZAVI-SHEARER, D., RAZAVI, H., SCHMELZER, J. & ALFALEH, F. Z. 2020. A tool to measure the economic impact of Hepatitis B elimination: A case study in Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health, 13, 1715-1723.

SANNATHIMMAPPA, M. B., NAMBIAR, V. & ARVINDAKSHAN, R. 2019. Hepatitis B: Knowledge and awareness among preclinical year medical students. Avicenna journal of medicine, 9, 43-47.

SETIA, S., GAMBHIR, R., KAPOOR, V., JINDAL, G., GARG, S. & SETIA, S. 2013. Attitudes and Awareness Regarding Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C Amongst Health-care Workers of a Tertiary Hospital in India. Ann Med Health Sci Res, 3, 551-8.

SUBAIEA, G., ALJOFAN, M., DEVADASU, V. & ALSHAMMARI, T. 2017. Acute toxicity testing of newly discovered potential antihepatitis B virus agents of plant origin. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research, 10, 210-213.

THOMPSON, M. J., TAYLOR, V. M., JACKSON, J. C., YASUI, Y., KUNIYUKI, A., TU, S. P. & HISLOP, T. G. 2002. Hepatitis B knowledge and practices among Chinese American women in Seattle, Washington. Journal of Cancer Education, 17, 222-226.

WANG, P. C., WEI, T. Y., TSENG, T. C., LIN, H. H. & WANG, C. C. 2017. Cirrhosis has no impact on therapeutic responses of entecavir for chronic hepatitis B. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 29, 946-950.

WHO 2022. (World Health Organization)., Hepatitis B. fact sheet available at https://www. who. int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b#:text= WHO% 20estimates% 20that% 20296% 20mi11ion, carcinoma% 20 (primary% 20liver% 20cancer). Accessed 30-08-2024.

YAU, A. H., FORD, J. A., KWAN, P. W., CHAN, J., CHOO, Q., LEE, T. K., KWONG, W., HUANG, A. & YOSHIDA, E. 2016. Hepatitis B Awareness and Knowledge in Asian Communities in British Columbia. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2016, 4278724.