Full Length Research Article - (2023) Volume 18, Issue 4

Personality Style And Its Relationship To Ostentatious Consumer Behaviour And Family Adjustment Among Saudi Women

Dr. Al-Farraj Hanan A**Correspondence: Dr. Al-Farraj Hanan A, Assistant Professor of Psychological Counseling, Department of Psychology-Faculty of Social Sciences, Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU, Saudi Arabia, Email:

Received: 08-Aug-2023 Accepted: 22-Aug-2023 Published: 22-Aug-2023

Abstract

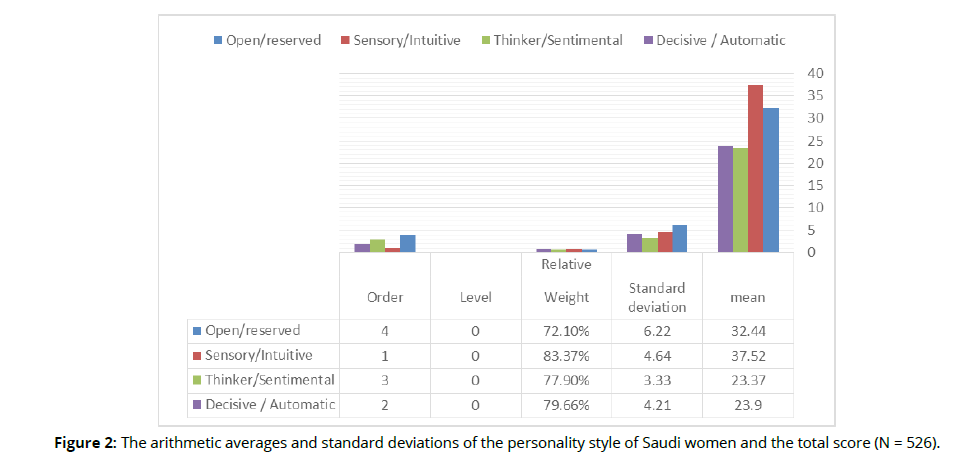

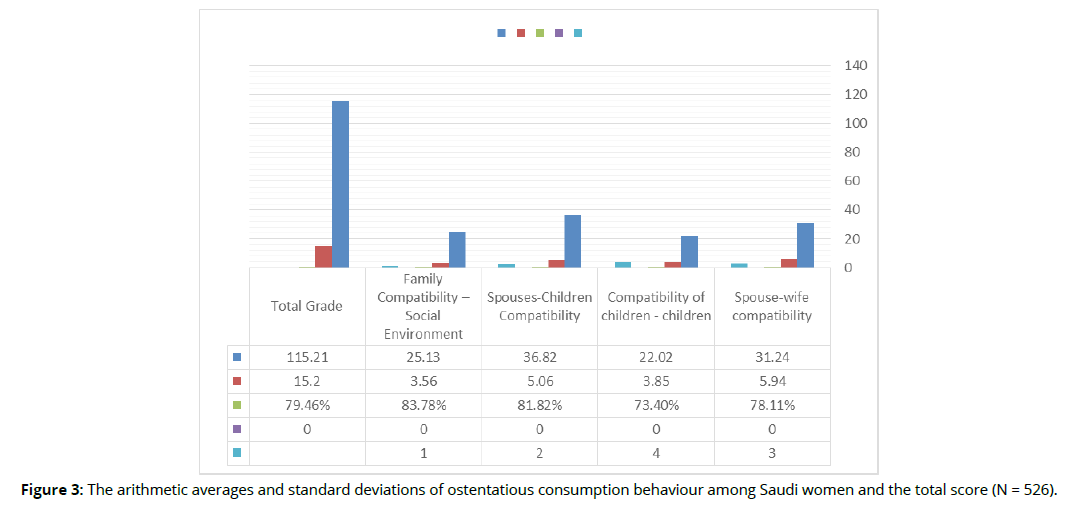

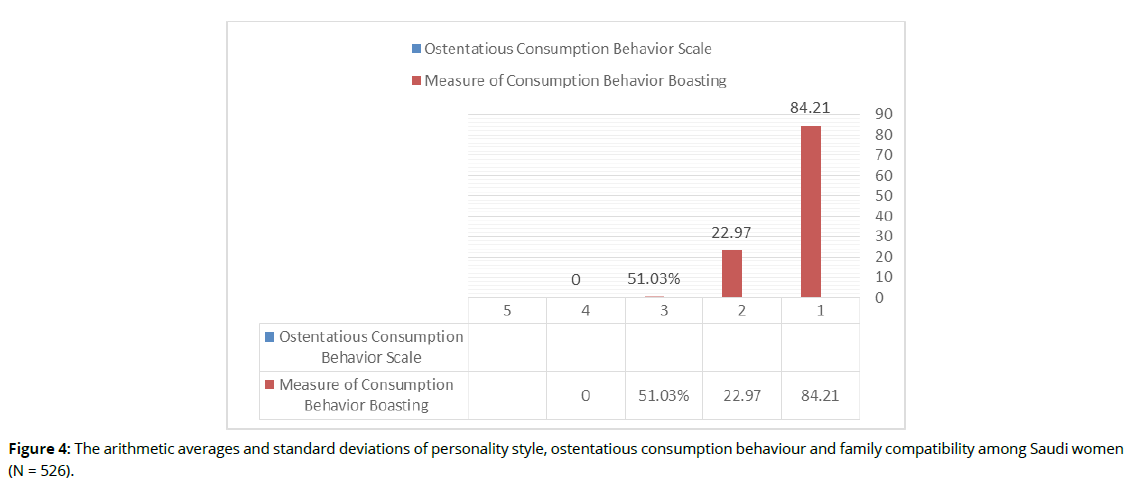

The current study aimed to identify the relationship between personality style, ostentatious consumption behaviour and family compatibility among Saudi women. The study sample consisted of 526 respondents and the results revealed that the most common personality type among the participants was sensory/ intuitive (mean 37.52), followed by decisive/automatic (mean 23.90) and open/conservative (mean 32.44). The level of ostentatious consumption behaviour was 84.21. Regarding the dimensional levels of the family compatibility scale among Saudi women, the social environment was the highest with an arithmetic average of 25.13, followed by the compatibility of spouses - children with an arithmetic average of 36.82 and the compatibility of children - children with an arithmetic average of 22.02. The arithmetic average of the scale as a whole was 115.21 with a relative weight of 79.46%. These results demonstrated a statistically significant positive relationship (p=0.01) between all dimensions of the personality style scale and the family compatibility scale and the total degree, except for the family compatibility dimension - social environment and the total score of the boasting consumption behaviour. There were differences in personality style according to several demographic variables (age, number of children, economic income, duration of marriage, educational level) but not in the family pattern according to educational level. There were also statistically significant differences in family compatibility according to the number of children, economic income, duration of the marriage, and nature of housing but no differences in the family style according to age and educational level, in relation to proud consumption behaviour (age, number of children, economic income, duration of marriage) or consumption behaviour according to nature of housing and educational level. Finally, the study results showed the possibility of predicting family compatibility through personality style with 25.5% of the variation explaining the dimensions of the personality style scale, and 12.2% of variance explaining the predictive behaviour of ostentatious consumption among Saudi women.

Keywords

Personality style. Conspicuous consumption behaviour. Family adjustment. Saudi women

Introduction

The personality and its pattern represent an integrated psychosomatic and social unit that grows through several stages, and the personality style is a special composition of certain similar traits, such as physical cognitive, and emotional traits. They differ from traits found in other styles (Khalifa, 2018) and play a clear role in the life of an individual. Many models explain the components of personality. Moreover, family and cultural factors are basic indicators of consumer behaviour, as the individual is affected by those around them and their culture is acquired in the society they are involved in, such as friend groups and social networks (Bahaa El-Din, 2020, p. 22).

Studies in consumption have gone beyond the economic vision concerned with consumption within the framework of the process of marketing goods and the factors affecting it with consumption as a variable in the economic process in terms of its link to demand and a focus on the social dimensions of consumption in terms of its link to social level and personality type and its impact on family compatibility and the degree of cohesion among family members. Regarding consumption, Klabi (2020) stated matching self-image with symbolic consumption (represented by phenotypic consumption and state consumption) and that the emotional attachment of the consumer to a high-status brand in particular, as they seek excellence and success through it on an individual level and not on social acceptance through the consumption. Al-Zahrani's study (2017) showed that the consumption pattern in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia generally tends to be luxury, as society consumes what is necessary and unnecessary in all fields. Al-Khamshi's study (2017) confirmed the impact of social and economic mobility on Saudi society and the spread of the consumption culture and the emergence of some class disparities between different social strata and extravagance in social events (Kishk, 2018) as indicated by Chaudhuri and Majumdar (2010).

The culture of consumption is different from what it was in the past, where the simple rational consumer has been replaced by a more complex consumer due to the increasing importance of self-images and social status. There is a link between the culture of consumption and personality style and self-concept. Indeed, Toth (2014) showed the role of self-concept in determining consumer behaviour, where most respondents preferred to see themselves looking better and self-satisfying through consumer products related to entertainment. One of the related aspects of ostentatious consumption is the personality pattern of the individual and its reflection on the level of family compatibility, as studies related to the psychological aspect indicate that different personality patterns, which are defined as a pattern or style that distinguish the personality of the individual from the personality of another individual through their personality characteristics, are clear through an individual’s actions and behaviours in all fields (Al-Hawari, 2017, 20).

Ostentatious consumption is represented by exaggerated spending according to the standards of consumer behaviour prevailing in society, such as spending on birthdays, success, marriage and engagement celebrations, which has been termed "phenotypic consumption". Wasting money on the purchase of expensive and rare goods not required for daily life helps the owner to appear, boast and pride, giving them prestigious social status as people considers them a member of the luxurious aristocracy; this brings happiness and may help the individual to acquire the social rights and privileges that characterise the affluent classes (Al-Ashry, 2018). The prevailing effects of the level of ostentatious consumer behaviour, as well as the personality style, are reflected in the life of women in general, the level of compatibility and family stability, and the ability of family members to achieve family happiness. All family members seek to maintain their stability and cohesion and the integrity of the relationship between parents, as well as between them and their children, as well as between their children, so that love and mutual respect prevail among all and the family establish mutual social relations with others (Hammam; Fikri; Emma M; Nofal, 2017, p. 261).

The importance of family compatibility is evident because it is linked to family stability, as the couple’s relationship and the extent to which there is compatibility between them affect family stability (Sahaf, 2015). For an individual to form a good and compatible family, they must have learned their behaviours in addition to family culture, as this is the basis from which they derive everything that benefits them throughout life from childhood to old age (Muhammad, Al-Zuhriand Ali, 2022).

Due to the lack of studies regarding the nature of the relationship between personality style and family stability, the current study examined the importance of the variables to determine the nature of the relationship between those variables, especially as they are related to the social changes in the construction and cohesion of the Saudi family, and the impact of globalisation and the need for women in light of global openness to follow a moderate and safe consumer culture to maintain family cohesion and stability, especially after its exit to the field of work and the realisation of Vision 2030 to empower them psychologically, economically and socially in all fields.

Theoretical framework and previous studies

Personality is a comprehensive framework that includes complex physical, mental and psychological features that include abilities, motives and culture. The trait is relatively stable or constant and repeated in a variety of situations that distinguish the individual from others. It determines the individual's style of thinking, feelings and tendencies, as well as their behaviour and interaction with others and the nature of their adaptation to situations (Al-Tayeb, 2022).Personality expresses the characteristics that distinguish people based on their unique thoughts and actions (Wood, 2012).

First: The personality style of Saudi women

Opinions have varied on the concept of personality and its different patterns as a complex term, as personality involves a set of relatively fixed psychological traits that affect the way an individual interacts with their environment. Zakar (2013) defined personality as one of the most comprehensive concepts in psychology because it contains all mental and physical qualities which interact, so no clear and specific meaning of personality has been reached, and it is a distinctive type of trait or pattern. It also expresses the sum of a person's motives, conflicts, preparations and instincts, as well as their conflicts and acquired preparations (Rabee, 2013). Personality is a set of relatively stable characteristics, explaining how an individual is distinguished from others, as a particular group cannot be limited to others. The personality style is the basic structure of an individual’s identity which is independent of others. Personality patterns have been divided into four separate dualities through which the individual's personality pattern is known (Cohen, Ormoy & Karen 2013).

Personality styles

The human personality consists of eight preferences distributed in four dimensions which are dimensions with opposite pairs of preferences distributed as follows:

1. Personality type (open/reserved): The owner of the open preference (extraversion) is symbolised by the symbol (E), and the individual prefers to focus on the outside world of other individuals and activities, directing their energies to the external environment, and receives energy from interacting with others. They are compatible with the external environment and prefer to communicate by talking to others and working to achieve their beliefs. They prefer to learn by doing various activities that bring benefit, and it is easy to initiate work and establish relationships with others, as they are characterised as a social individual, not an introvert. Regarding reservation (introversion), it is denoted by the symbol (I), and the individual prefers to focus on the inner world associated with their thoughts and experiences, directing their energies and attention inward, so they also get energies from thinking about their memories, feelings and experiences. The individual who had a conservative personality is characterised by focusing on communicating with others by writing and reflecting on what is around them more than seeking to work realistically. They also focus on their interest and do not take matters into account unless it is very important.

2. Personality type (sensory/intuitive): The owner of the sensory preference (sensing) is symbolised by the symbol (S) and they prefer to sense reality, take information in its real form, and know the details about it to understand the practical reality they live. The individual who prefers the sensory personality is characterised by having a constant desire to know concrete facts, focus on the real thing, and remember the fine details, while the owner of intuition preference (intuition), symbolised by the symbol (N), prefers to take information through their vision of things from the perspective of their sense of things, focusing on the relationships and connections between facts to deduce what they want without reference to the practical reality he lives, and obtain information within their perception, awareness of possibilities, and attitudes. The intuitive individual is characterised by thinking about future life possibilities, imagining, and innovating verbally and not practically, as well as focusing on the patterns and meanings of the data they reach, remembering the details of a matter when they connect to a certain pattern and drawing conclusions based solely on intuition.

3. Personality type (thinker/sentimental): The owner of the thinking preference is symbolised by the symbol (T), and they prefer to think to reach a judgment by looking at the logical consequences of choosing a decision or a specific action, as their judgment is rational, after studying the pros and cons, criticising and analysing the errors to solve any problem which may arise to find a standard that is applied in all similar cases. The individual is characterised by a preference, the thinking personality, that they use to analyse the data and information in the search for the causes and influences that may affect their judgment logically, seeking to solve the problems and difficulties logically and analytically to find an objective standard for similar cases. Regarding the owner of emotional preference (feeling), which is symbolised by the symbol (F), they prefer to use their feelings and conscience to judge and make a decision, feeling energetic and energetic when they perceive support from others and receive praise. Their goal is to create harmony with others and treat each individual as unique. The individual with an emotional personality type is characterized by being sympathetic to others, always seeking to achieve harmony, positive relationships with others, compassion and tenderness for others, and justice because they want to be treated as an individual in the community.

4. Personality style (automatic decisive): The decisive personality style (judgment) is symbolised by the symbol (J) and the individual prefers to be decisive in making any decision related to the outside world in which they live to plan and successfully organise their life. In most cases, the individual is organised and wants to do things according to a plan and a schedule to ensure that the things they seek to achieve are accomplished. The individual with a decisive personality is characterised by being a well-organised, decisionmaker. They are systematic in making short- and long-term plans to get things organised in an orderly way and avoid any last-minute pressure. The automatic personality style (perception) is symbolised by the symbol (P) and the individual prefers to live spontaneously and flexibly, always seeking to understand life simply and easily. They also make plans but separately from any decisions, preferring to keep their choices and decisions clear. They are characterised by an ability to adapt to the requirements of the current era. The individual with an automatic personality is characterised by being spontaneous, flexible, clear to all, quick to adapt to others, accepts changing their mind and working who does, and coping with any last-minute pressures (Tashtoush, 2022; Al-Hawari, 2017; Al-Sharifeen, Al-Sharifeen and Al-Daqqas, 2012).

Second: The ostentatious consumption behaviour of Saudi women

Consumption culture can be defined as "part of the general culture formed from a set of symbols, shapes, and images driving the consumer process, as they appear in the consumer lifestyle, such as cars or the use of international brands, and attention to them such as clothes, perfumes, watches, etc., and the pattern of spending daily and weekly leisure time" (Al-Ashry, 2018, p. 592). For Wang and Foosiri, ostentatious consumption behaviour is defined as a broad concept under which three basic elements fall including being good, expensive, and not necessary products or services that can be purchased by a consumer with a high income, with limited demand and high value, which enhances the consumer's identity.

Many variables and factors have influenced the consumption of Saudi women in disparate social classes as one of the most important forms of the family. Although patterns based on ostentatious consumption, or so-called phenotypic consumption, have existed since ancient times, they emerged through the writings of Veblen (1899), who addressed the behavioural characteristics of the wealthy social class who emerged as a result of the accumulation of capital during the Second Industrial Revolution. Jain and Sharma (2018) highlighted that this consumption was only for the rich, however, since the early nineties and economic recovery, economic growth has led to the consumption of luxuries and expensive luxury goods as a reinforcement or as an expression of social status (Truong et al., 2008). Consumption patterns have varied and the trend towards luxury consumption has increased (Bögenhold & Naz, 2018). It is no longer a phenomenon characteristic of the upper classes and the wealthy, it has come to include low-income classes (Memushi, 2013). Therefore, this has resulted in measuring the level of the individual socially as much as they consume goods and services, even if they are useless. One of the manifestations of ostentatious consumption in Saudi society is the spending on cosmetics of 8.53 billion dollars in 2021 (Mordor Intelligence, 2019). A study (Abu Nab, 2019) of luxury fashion consumers found that Saudi women's consumption of fashion, especially on important occasions, is strongly affected by comparison and competition which stimulates the creation of a distinctive identity of dress that reflects wealth, social status and receiving compliments, and that excellence and luxury are values entrenched in the Saudi fashion consumption system. Saudi women's demand for gold and jewellery constitutes 1.7% of the total global demand, with the highest demand for gold and jewellery in 2015, accounting for 2.8% of the total global demand (World Gold Council, 2019).

Regarding studies of the ostentatious consumption behaviour of Saudi women, Al-Maliki's study (2020) aimed to identify the impact of recreational activities on family values. The study was conducted on a sample of families in Jeddah city (n=114) and indicated a shift in the consumption pattern of members of society and the beginning of rational economic behaviours concerned with planning family expenses and working to adhere to specific spending before even the needs of family members as a whole can be met within the limits of available income. of Al-Rashoud (2018) aimed to identify the most important sources of income, aspects of household expenditure and the factors affecting luxury consumption in Saudi society, showing that the quality of the commodity, its price, characteristics, and the credibility of information about it are among the most important factors affecting consumer decisions. Entertainment consumption is more affected by advertisements that promote a culture of ostentation and simulation. The study also identified the negative effects of luxury consumption, which are waste, children's poor sense of the value of money, depletion of family resources, and the transformation of consumption into a pathological state. Bani-Rshaida and Alghrabeh (2017) demonstrated a positive relationship between compulsive buying disorder and depressive symptoms in a sample of consumers. Zhang, Brook, Leukefeld, De La Rosa, and Brook (2017) also reported an inverse correlation between addictive buying and quality of life and that the more addictive purchase, the lower the quality of life. It also had negative effects on family income as its misuse entails many financial, family and psychological problems. Al-Sayed's (2016) study also indicated that the more addictive buying, the lower the self-esteem that is, purchasing behaviour may be associated with personality style and traits.

Third: Family compatibility among Saudi women

Family compatibility is an important requirement for all members of society, especially working women, and it is an indicator of the lack of increase in divorce rates and marital disorders. Family compatibility is defined as “the ability of family members to achieve cohesion and stability, overcome the problems they face, and establish social relations characterised by love and giving between spouses, between parents, children and between children and each other”. This requires compatibility between spouses, which is characterised by mutual respect between spouses, exchange of views and ideas, and sharing in family responsibilities, as well as compatibility between parents and children through a relationship of love and respect, and compatibility between children and each other through the prevalence of love, tolerance, cooperation, nonquarrel and self-love, so tension and compatibility prevail between its members (Mohammed; Al-Zuhri & Ali, 2022). Family compatibility is represented in the appropriate choice of partner and preparation for married life, which exists between two married people who tend to avoid problems or solve those problems, accept mutual feelings, participate in tasks and activities, and achieve harmony between them (Hammam; Fikri; Imam; & Nofal, 2017).

Dimensions of family compatibility

The dimensions of family compatibility are divided into:

1. Compatibility between spouses: The interaction between spouses is based on love, affection and satisfying basic and secondary needs, and the agreement of the spouses and harmony provides the basis for building a strong and stable family; without this stability, there can be no cohesive family.

2. Compatibility between parents and children: The extent to which family members are harmonious with each other and the relationships of love, affection, support and cooperation between them together achieve a happy and satisfying family life so that they can achieve desirable relationships represented in understanding, interdependence and mutual respect between all.

3. Compatibility between children and each other: The relationship between brothers in the same family is based on affection, love and cooperation but they may be exposed to some problems and disputes that end and disappear with their age.

4. Compatibility with family, relatives and others: Family members can establish normal and continuous social contacts characterised by cooperation, love, keeping pace with social norms, including happiness with others, and commitment to the ethics of society (Hammam; Fikri; Imam; Nofal, 2017, 262).

Starkey (1991) dealt with the knowledge of the relationship between the income of the working wife and family instability, which is associated with family compatibility. The study involved 1588 families and indicated that there is a slight impact of the wife's income in marital instability which according to the husband's characteristics, such as the husband's irritability and his ability to control and the burden of roles borne by the working wife compared to the non-working wife resulting from the spouse's lack of cooperation and adherence to his traditional role of working only outside the home.

Study problem

The study of personality is a major source for understanding behaviour and trying to predict and analyse it. Personality expresses the individual’s pattern of behaviour and way of thinking that distinguishes them from others and is a product of the interaction of their mood, mind and body structure tracts, which determines the unique compatibility of their environment, which is the entrance to the interpreter of the principle of individual differences between community members and explains the variation in impressions, behaviour, tendencies, etc., whereby personality traits affect the shopping process, for example, Yusuf, Sukati & Adenyang (2016). Young believes that an individual's personality consists of a set of preferences, therefore each individual can fall in one of two opposite directions, as an extrovert and conservative, and that the individual has four psychological functions, which are sensory and intuitive, and thinking and conscience. These functions interact with one of the two directions (extroverted, reserved) so that there are eight expected personality preferences, and the individual has one of these preferences according to their personality which distinguishes them from other individuals even if they hold the same personality style; this indicates integration of the different psychological functions that make up the personality of the individual (Tashtosh, 2022).

The exit of women to work and the resulting many family problems have led to multiple issues, the most important of which is the difficulty of compatibility between duties and responsibilities, especially regarding family compatibility and the nature and pattern of their personality, which may result in the emergence of some problems related to the lifestyle, including those related to the nature of consumption, which may turn into ostentatious behaviour that affects family compatibility and may lead to family disorders. Individual behaviours allow the individual to adapt to changes, which requires attention to the effects of ostentatious consumption and its impact on family relations, and enlightening families, especially women, about the values of saving, and its positive role while fighting negative values and practices that instil in women the addiction to ostentatious consumption without considering its effects on family burden, cohesion and harmony. Some studies have shown an association between an open personality and a desire to shop without regard to its type (Lissitsa, & Kol, 2021) and that personality traits predict the buying rush (Lixăndroiu, Cazan, & Maican, 2021). Therefore, the current study was designed to investigate the personality pattern and its relationship to ostentatious consumption behaviour and family compatibility among Saudi women. To the author’s best knowledge, no study has linked the variables in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and light of the global openness represents a central market. Global luxury brands and making Saudi women vulnerable to influence pretend consumption either a desire to obtain social status or a way to deal with pressures and frustrations and escape from unpleasant situations and emotions and low self-esteem, which requires understanding the different personality patterns and its impact on the behaviour of phenotypic consumption and knowing its motives, despite the difficult economic conditions of some income groups that are addicted to this type of consumption, which may threaten the family entity and cohesion.

Methodology

Method

To achieve the study objectives, a descriptive (correlational) approach was used to identify the relationship between the dimensions of personality type and the ostentatious consumption behaviour and family compatibility (subdimensions and total degree) of the working woman, as well as to identify the effect of the independent variable (personality type) predictive of ostentatious consumption behaviour and family compatibility on the two predicted dependent variables.

Sample

The study population (n=526) consisted of Saudi women in Riyadh randomly selected through an electronic link who met the following inclusion criteria: 1. consent to participate in the study; 2. the application of demographic variables to the target group; 3. a Saudi national and reside in the city of Riyadh during the study period; 4. a married woman. The distribution of the respondents according to the demographic variables is shown in Figure 1.

Study tools

1. Personality style scale: The personality type scale prepared by Al- Hawari (2017), Al-Sharifeen, Al-Sharifeen and Al-Daqs (2018) was used in the current study. The scale consisted of 31 items distributed in four dimensions: open-minded conservative (1-9), sensory/intuitive (10-18), emotional thinker (19-24), and decisive/automatic (25-30). For the purposes of the current study, the content of the tool was validated by presenting it to a group of professors specialised in Arabic and foreign languages, measurement and psychological evaluation, to verify the authenticity of the tool in its current form after translating and modifying the paragraphs in terms of linguistic wording. The correlation coefficients (Pearson) of the current tool were determined by the scores of each statement and the total scores of an exploratory sample (n=62) similar to the study sample and the correlation coefficients for the first dimension ranged between 0.79−0.56 and 0.83−0.54, the third dimension 0.60−0.82 and the fourth dimension 0.88−0.70, all of which were statistically significant, thus considered true to what they were developed to measure. The Cronbach alpha coefficient and the half-hash were calculated and ranged between 0.84, 0.87, 0.79, and 0.89 respectively, while the dimensions by the half-fractionation method (0.89, 0.93, 0.92, 0.93) were acceptable stability ratios. The tool was scored using a five-point Likert scale as follows: Strongly disagree (1) Disagree (2), Neutral (3), Agree (4), and Strongly agree (5). The higher the score, the higher the indication that this preference is prevalent in the field, and the personality style is determined by the largest degree for each area of personality styles with a four-letter code such as ESTJ, ENTP, ISTP, and SINTP.

2. The ostentatious consumption behaviour scale was the tool prepared by Roy Chaudhuri, Mazumdar, and Ghoshal (2011), which was translated and coded for the Arab environment for the purposes of the current study. The final form consists of 33 items and the authenticity of the tool was verified as follows: 1. the content of the tool was presented to a group of professors specialised in Arabic and foreign language, measurement and psychological evaluation, to verify the validity of the tool in its current form after translating and modifying the paragraphs in terms of linguistic wording; 2. calculating the correlation coefficients (Pearson) for each phrase of the scale and the total scores of the scale on an exploratory sample (n=62) similar to the study sample (ranged between 0.52–0.89 and were statistically significant and thus, the scale phrases were considered true to what was developed to measure. The stability coefficient of the scale reached the Cronbach alpha method (0.965), and the half-segmentation method (0.966), which is a high stability ratio, confirming the applicability of the scale.

3. The family compatibility scale used was prepared by Al-Hawari (2017). This scale consists of 29 items distributed on four dimensions: the compatibility of the husband/wife consisting of 8 paragraphs, the compatibility of children/children consisting of 6 paragraphs, the compatibility of the spouses/ children consisting of 9 paragraphs, and the compatibility of the family/the social environment consisting of 6 paragraphs. The authenticity of the tool was verified as follows: 1. The content of the tool was validated by presenting it to a group of professors specialised in Arabic and foreign languages, measurement and psychological evaluation, to verify the authenticity of the tool in its image current after translating and modifying paragraphs in terms of linguistic wording; 2. calculating the correlation coefficients (Pearson) of the current tool using an exploratory sample (n=62) similar to the study sample, where the values of the correlation coefficients for the first dimension ranged between 0.53−0.83, the values of the third dimension were 0.53-0.86 and the values of the fourth dimension were 0.58−0.79. All of them were statistically significant, and thus the statements of the scale are considered true to what was developed to measure. The structural honesty of the scale was evaluated by calculating the correlation coefficient between the total scores of each dimension of the scale and the total degree of the scale, and the values of the correlation coefficients ranged between 0.80–0.84; all were statistically significant. The alpha coefficient of Cronbach and the half fractionation were calculated, ranging between 0, 95, 0.78, 0.88, and 0.81, respectively, for the dimensions and 0.94 for the total degree of the instrument, while for the dimensions by the half-fractionation method were 0.96, 0.73, 0.93, and 0.96, and 0.96 for the whole tool, which are acceptable stability ratios. The scale was scored using a five-point Likert scale as follows: absolutely (1), rarely (2) sometimes (3), often (4) and always (5). These total scores ranged from 29 to 145 and a score of 2.49 or less indicated a low level of family compatibility, 2.50−3.49 indicated an average level of family compatibility and 3.50 or more indicated a high level of family compatibility.

Results

1. The relationship between personality type dimensions and ostentatious consumption behaviour and family compatibility (subdimensions and total score) in working women

Table 1 shows the statistically significant positive relationship (p=0.01) between all dimensions of the personality style scale and the family compatibility scale and the total score, except for the family compatibility dimension - social environment and the total score of the boasting consumption behaviour scale, and the total score of the boasting consumption behaviour scale (Table 1).

| Dimensions of the personality style scale | Dimensions of the family compatibility scale | Flaunting consumption scale | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spouse-wife compatibility | Son-Sons Compatibility | Spouses-Children Compatibility | Family Compatibility – Social Environment |

Total Grade | ||

| Open/reserved | 0.197** | 0.376** | 0.250** | 0.174** | 0.296** | 0.335** |

| Sensory/Intuitive | 0.262** | 0.316** | 0.349** | 0.264** | 0.360** | 0.187** |

| Thinker/Sentimental | 0.316** | 0.403** | 0.354** | 0.236** | 0.399** | 0.150** |

| Decisive/Automatic | 0.284** | 0.313** | 0.365** | 0.268** | 0.374** | 0.204** |

| Measure of Consumption Behaviour Boasting | 0.125** | 0.252** | 0.144** | 0.061 | 0.175** | - |

2. Levels of personality style, ostentatious consumptionbehaviour, and family compatibility among Saudi women

Figure 2 shows that the sensory/intuitive dimension ranks the highest with an arithmetic average of 37.52 and a relative weight of 83.37%, followed by the open/conservative dimension with an arithmetic average of 23.90 and a relative weight of 79.66%, thinker/emotional with an arithmetic average of 23.37 and a relative weight of 77.90%, and open/conservative with an arithmetic average of 32.44 and a relative weight of 72.10% (Figure 2).

Figure 3 shows that the compatibility of the family - the social environment came the highest with an arithmetic average of 25.13 and a relative weight of 83.78%, followed by the compatibility of spouses-children with an arithmetic average of 36.82 and a relative weight of 81.82%, then the compatibility of the husband-wife with an arithmetic average of 31.24 and a relative weight of 78.11%, and the compatibility of children-children with an arithmetic average of 22.02 and a relative weight of 73.40%. The arithmetic mean of the scale as a whole was 115.21 with a relative weight of 79.46% and all dimensions of the scale were high (Figures 3).

Figure 4 shows the arithmetic mean of the ostentatious consumption behaviour scale as a whole was 84.21 with a relative weight of 51.03% and a low level (Figure 4).

3. Differences between the averages of personality style, family compatibility and ostentatious consumption behaviour among Saudi women according to demographic variables

Table 2 shows that there were statistically significant differences (p<0.05) according to age in the total score of dimensions in the personality style scale in favour of the age group from 25 to less than 30 years, followed by the age group from 30 to less than 35 years. There were also statistically significant differences (p<0.05) according to the number of children in most dimensions of the personality style scale, while there were no statistically significant differences in the thinking/emotional dimension. The differences came at the level of the total degree in favour of the group that had 4−7 children, followed by a thousand hundred that have 3 children or less. There were statistically significant differences (p<0.05) according to the economic income in most dimensions of the personality style scale, while there were no statistically significant differences in the thinking/emotional dimension. The differences came at the level of the total degree in favour of those with an economic income of less than 5000 riyals. There were statistically significant differences (p<0.05) according to the duration of marriage in the thinking/ emotional dimension in favour of those who were married less than 5 years, followed by 5−10 years, while there are no statistically significant differences in the remainder of the dimensions of the personality style scale. There were statistically significant differences (p<0.05) according to educational level in the sensory/intuitive dimension in favour of postgraduate graduates, while there were no statistically significant differences in the rest of the dimensions of the personality style scale. Also, there were no statistically significant differences according to the nature of housing in the dimensions of the personality style scale (Tables 2 & 3).

| Contrast source | sum squares | DF | medium squares | F | Sig | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Open/reserved | 672.33 | 3 | 224.11 | 6.384 | 0.001 |

| Sensory/Intuitive | 185.91 | 3 | 61.97 | 3.058 | 0.028 | |

| Thinker/Sentimental | 228.36 | 3 | 76.12 | 7.178 | 0.001 | |

| Decisive/Automatic | 175.71 | 3 | 58.57 | 3.513 | 0.015 | |

| Number of children | Open/reserved | 359.59 | 2 | 179.79 | 5.122 | 0.006 |

| Sensory/Intuitive | 160.21 | 2 | 80.10 | 3.953 | 0.020 | |

| Thinker/Sentimental | 29.22 | 2 | 14.61 | 1.378 | 0.253 | |

| Decisive/Automatic | 104.61 | 2 | 52.31 | 3.137 | 0.044 | |

| Living | Open/reserved | 181.61 | 2 | 90.81 | 2.587 | 0.076 |

| Sensory/Intuitive | 32.44 | 2 | 16.22 | 0.801 | 0.450 | |

| Thinker/Sentimental | 3.16 | 2 | 1.58 | 0.149 | 0.862 | |

| Decisive/Automatic | 18.69 | 2 | 9.34 | 0.560 | 0.571 | |

| Level of economic income |

Open/reserved | 582.16 | 2 | 291.08 | 8.292 | 0.001 |

| Sensory/Intuitive | 156.48 | 2 | 78.24 | 3.861 | 0.022 | |

| Thinker/Sentimental | 41.63 | 2 | 20.82 | 1.963 | 0.141 | |

| Decisive Automatic | 286.61 | 2 | 143.30 | 8.595 | 0.001 | |

| Duration of marriage |

Open/reserved | 229.50 | 2 | 114.75 | 3.269 | 0.039 |

| Sensory/Intuitive | 2.80 | 2 | 1.40 | 0.069 | 0.933 | |

| Thinker/Sentimental | 13.02 | 2 | 6.51 | 0.614 | 0.542 | |

| Decisive/Automatic | 143.44 | 2 | 71.72 | 4.301 | 0.014 | |

| Education level | Open/reserved | 200.66 | 2 | 100.33 | 2.858 | 0.058 |

| Sensory/Intuitive | 197.81 | 2 | 98.91 | 4.881 | 0.008 | |

| Thinker/Sentimental | 14.67 | 2 | 7.33 | 0.692 | 0.501 | |

| Decisive/Automatic | 36.69 | 2 | 18.35 | 1.100 | 0.334 | |

| Error | Open/reserved | 17903.05 | 510 | 35.10 | ||

| Sensory/Intuitive | 10334.96 | 510 | 20.26 | |||

| Thinker/Sentimental | 5408.18 | 510 | 10.60 | |||

| Decisive/Automatic | 8503.57 | 510 | 16.67 | |||

| All | Open/reserved | 574042.00 | 526 | |||

| Sensory/Intuitive | 751646.00 | 526 | ||||

| Thinker/Sentimental | 293072.00 | 526 | ||||

| Decisive/Automatic | 309678.00 | 526 | ||||

| Contrast source | sum squares |

DF | medium squares |

F | Sig | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Spouse-wife compatibility | 179.90 | 3 | 59.97 | 1.795 | 0.147 |

| Compatibility of children - children | 55.18 | 3 | 18.39 | 1.346 | 0.259 | |

| Spouses-Children Compatibility | 64.47 | 3 | 21.49 | 0.866 | 0.459 | |

| Family Compatibility – Social Environment | 86.88 | 3 | 28.96 | 2.351 | 0.072 | |

| Total Grade | 317.19 | 3 | 105.73 | 0.481 | 0.696 | |

| Number of children |

Spouse-wife compatibility | 77.37 | 2 | 38.69 | 1.158 | 0.315 |

| Compatibility of children - children | 54.69 | 2 | 27.34 | 2.001 | 0.136 | |

| Spouses-Children Compatibility | 12.83 | 2 | 6.41 | 0.258 | 0.772 | |

| Family Compatibility – Social Environment | 76.06 | 2 | 38.03 | 3.087 | 0.046 | |

| Total Grade | 417.46 | 2 | 208.73 | 0.949 | 0.388 | |

| Living | Spouse-wife compatibility | 41.06 | 2 | 20.53 | 0.615 | 0.541 |

| Compatibility of children - children | 0.28 | 2 | 0.14 | 0.010 | 0.990 | |

| Spouses-Children Compatibility | 60.31 | 2 | 30.15 | 1.215 | 0.298 | |

| Family Compatibility – Social Environment | 75.74 | 2 | 37.87 | 3.074 | 0.047 | |

| Total Grade | 443.76 | 2 | 221.88 | 1.009 | 0.365 | |

| Level of economic income | Spouse-wife compatibility | 168.16 | 2 | 84.08 | 2.517 | 0.082 |

| Compatibility of children - children | 154.65 | 2 | 77.32 | 5.659 | 0.004 | |

| Spouses-Children Compatibility | 245.72 | 2 | 122.86 | 4.950 | 0.007 | |

| Family Compatibility – Social Environment | 38.58 | 2 | 19.29 | 1.566 | 0.210 | |

| Total Grade | 2001.53 | 2 | 1000.76 | 4.549 | 0.011 | |

| Duration of marriage |

Spouse-wife compatibility | 32.24 | 2 | 16.12 | 0.483 | 0.617 |

| Compatibility of children - children | 157.92 | 2 | 78.96 | 5.779 | 0.003 | |

| Spouses-Children Compatibility | 102.76 | 2 | 51.38 | 2.070 | 0.127 | |

| Family Compatibility – Social Environment | 29.71 | 2 | 14.85 | 1.206 | 0.300 | |

| Total Grade | 836.82 | 2 | 418.41 | 1.902 | 0.150 | |

| Education level | Spouse-wife compatibility | 149.92 | 2 | 74.96 | 2.244 | 0.107 |

| Compatibility of children - children | 40.57 | 2 | 20.29 | 1.485 | 0.228 | |

| Spouses-Children Compatibility | 63.00 | 2 | 31.50 | 1.269 | 0.282 | |

| Family Compatibility – Social Environment | 35.87 | 2 | 17.93 | 1.456 | 0.234 | |

| Total Grade | 905.52 | 2 | 452.76 | 2.058 | 0.129 | |

| Error | Spouse-wife compatibility | 17038.29 | 510 | 33.41 | ||

| Compatibility of children - children | 6968.37 | 510 | 13.66 | |||

| Spouses-Children Compatibility | 12658.81 | 510 | 24.82 | |||

| Family Compatibility – Social Environment | 6282.69 | 510 | 12.32 | |||

| Total Grade | 112191.34 | 510 | 219.98 | |||

| All | Spouse-wife compatibility | 531966.00 | 526 | |||

| Compatibility of children - children | 262794.00 | 526 | ||||

| Spouses-Children Compatibility | 726462.00 | 526 | ||||

| Family Compatibility – Social Environment | 338896.00 | 526 | ||||

| Total Grade | 7103386.00 | 526 | ||||

Table 4 shows that there were statistically significant differences (p<0.05) according to age in the ostentatious consumption behaviour scale in favour of the group aged 25−30 years, followed by the group aged 30−35 years. There were statistically significant differences (p<0.05) according to the number of children in the measure of ostentatious consumption behaviour in favour of the group that had 1−3 children, followed by the group that had 8 children or more. There were no statistically significant differences according to the rest of the variables in the measure of ostentatious consumption behaviour (Table 4).

| Contrast source | sum squares | DF | medium squares | F | Sig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 8156.04 | 3 | 2718.68 | 5.661 | 0.001 |

| Number of children | 4527.87 | 2 | 2263.93 | 4.714 | 0.009 |

| Living | 155.33 | 2 | 77.67 | 0.162 | 0.851 |

| Level of economic income | 3502.89 | 2 | 1751.44 | 3.647 | 0.027 |

| Duration of marriage | 976.83 | 2 | 488.42 | 1.017 | 0.362 |

| Education Level | 635.90 | 2 | 317.95 | 0.662 | 0.516 |

| Error | 244935.18 | 510 | 480.27 | ||

| All | 4006604.00 | 526 |

4. Predicting ostentatious consumption behaviour and family compatibility among Saudi women through personality style

Table 5 shows that the coefficient of determination is equal to 0.255, which means that 25.5% of the dimensions of the personality style scale can predict family compatibility. It is clear that there is a relationship between both variables (dimensions of the personality style scale and family compatibility), which indicates the significance of the regression model. The value of "P" is 37.72, which is statistically significant (p=0.001), and this indicates that the variation in the level of family compatibility is due to real variation and cannot be attributed to coincidence. Also, the dimensions of the personality style scale explain about 25.5% of the variation in the level of family compatibility, and the dimensions of the personality style scale predicted by family compatibility can be clarified as follows: (Table 5)

| Variable | Contrast source | Sum of squares | DF | Average squares | F | (R2) | sig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimensions of the personality style scale | Regression | 27231.17 | 4 | 6807.79 | 37.72 | 0.225 | 0.001 |

| Error | 94020.98 | 521 | 180.46 | ||||

| Total | 121252.15 | 525 |

Table 6 shows that the thinker/emotional variable has the highest correlation with family compatibility, as it reached a beta value of 0.22 with a regression coefficient of 0.98, and the value of "T" is 4.21, which is statistically significant (p=0.001), followed by the decisive/automatic variable with a beta value of 0.20, a regression coefficient of 0.72, and a value of "T" of 4.39, which is statistically significant (p=0.001). The open/conservative variable had a beta value of 0.11, a regression coefficient of 0.28, and a value of "T" was (2.65), which is statistically significant (p=0.008), followed by the sensory/intuitive variable with a beta value of 0.8, a regression coefficient of 0.27, and a value of "T" of 0.158, which is not statistically significant, which indicates a significant effect of this variable (Table 6).

| Dependent variable | Predictive variables (explained) | Regression coefficient (B) |

Standard error | Beta | (T) | Sig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental Compatibility |

Regression constant | 55.66 | 5.16 | 10.79 | 0.001 | |

| Open/reserved | 0.28 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 2.65 | 0.008 | |

| Sensory/Intuitive | 0.27 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 1.58 | 0.114 | |

| Thinker/Sentimental | 0.98 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 4.21 | 0.001 | |

| Decisive/Automatic | 0.72 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 4.39 | 0.001 |

Table 7 indicates that the coefficient of determination is equal to 0.122, which means that 12.2% of the dimensions of the personality style scale can predict the behaviour of ostentatious consumption J. It is clear that there is a relationship between both variables (dimensions of the personality style scale and ostentatious consumption behaviour J), which indicates the significance of the regression model, and the value of "P" is 18.07, which is statistically significant (p=0.001), and thus the variation in the level of ostentatious consumption behaviour J is due to a real variation and cannot be attributed to coincidence, and that the dimensions of the personality style scale explain about 12.2% of the variation in the level of ostentatious consumption behaviour, and the dimensions of the personality style scale predicting ostentatious consumption behaviour can be clarified as follows: (Table 7)

| Variable | Contrast source | Sum of squares | DF | Average squares | F | (R2) | sig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimensions of the personality style scale | Regression | 33737.20 | 4 | 8434.30 | 18.07 | 0.122 | 0.001 |

| Error | 243244.63 | 521 | 466.88 | ||||

| Total | 276981.83 | 525 |

Table 8 shows that the open/conservative variable has the highest correlation with ostentatious consumption behaviour, with a beta value of 0.30, a regression coefficient of 1.09, and the value of "T" was 6.41, which is statistically significant (p=0.001). This is followed by the decisive/automatic variable with a beta value of 0.10, a regression coefficient of 0.52, and a value of "T" of 1.97, which is statistically significant (p<0.05). After that, the sensory/intuitive variable has a beta value of 0.03, a regression coefficient of 0.16, and a value of "T" of 0.57, which is not statistically significant, indicating the existence of a significant effect of this variable. The thinker/emotional variable with a beta of -0.02, regression coefficient of -0.13, and a value of "T" of 0.35, which is not statistically significant, also indicating the existence of a significant effect of this variable and that the extroverted/reserved personality type is highly correlated with ostentatious consumption behaviour (Table 8).

| Dependent variable | Predictive variables (explained) | Regression coefficient (B) |

Standard error | Beta | (T) | Sig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boastful consumption behaviour | Regression constant | 33.50 | 8.30 | -- | 4.04 | 0.001 |

| Open/reserved | 1.09 | 0.17 | 0.30 | 6.41 | 0.001 | |

| Sensory/Intuitive | 0.16 | 0.28 | 0.03 | 0.57 | 0.571 | |

| Thinker/Sentimental | -0.13 | 0.38 | -0.02 | -0.35 | 0.726 | |

| Decisive/Automatic | 0.52 | 0.26 | 0.10 | 1.97 | 0.05 |

Discussion

The results of the study indicated that there is a statistically significant positive relationship between all dimensions of the personality style scale and the family compatibility scale and the total score, except for the family compatibility dimension - social environment, and the total score of the boasting consumption behaviour scale. This indicates that the desire to lean towards ostentatious consumption growth is associated with all personality styles, possibly due to the Saudi consumer's emotional attachment to the brand of particularly high status, as they seek excellence and phenomenological success through it - on the individual level - and not on social acceptance through consumption. This is consistent with the results of Al-Maliki’s study (2020). A shift in the consumption pattern of members of society and the beginning of rational economic behaviours concerned with planning family expenses and working to adhere to predetermined spending so that the needs of family members as a whole can be met within the limits of available income. This was unlike the rest of the dimensions of family harmony that are more vulnerable to the pattern of modernisation, development, change and the tendency towards a pattern of ostentatious consumption.

The variation in personality styles can be explained by the enjoyment of the respondents with high personality patterns that are all clearly described and that each participant responds differently to life situations and life and societal impressions. Furthermore, the study sample was most characterised as sensory/intuitive in the sense that they have a sense of reality and take information in its real form, with a constant desire to know concrete facts. Such individuals are characterised by being realistic and always focusing on the real and actual thing, as well as remembering the fine details to accordingly builds practical realistic conclusions. They realise ideas and theories through applications and practical experiments, focusing on the relationships and connections to form conclusions without reference to the practical reality. They want to obtain information within their perception and have an awareness of the possibilities. This may play a major role in influencing the practice of consumption patterns as well as family compatibility that tends towards stability and the desire to maintain family cohesion and structure. The next most common was the decisive/automatic personality pattern, which indicates that the respondents enjoy successful planning and organisation, avoid pressures, and even adapt to them and have the ability to adapt to the requirements of the times (Tashtosh, 2022; Al-Hawari, 2017; Al-Sharifeen, Al-Sharifeen & Al-Daqqas, 2012). These traits may reflect negatively on the practice of ostentatious consumption behaviour, which may reach the point of decline or the desire to practice more disciplined and realistic consumption behaviours.

The variation of the arithmetic averages of the family compatibility scale can be explained by the enjoyment of all respondents with high levels of family compatibility as well as in the dimensions that make it up, which indicates the ability of the participants to achieve cohesion and stability and overcome the problems they face and establish social relations characterised by love and giving between spouses, parents, and children. They feel the importance of family compatibility, it is an important requirement for all members of society. They can achieve cohesion and stability, overcome problems and establish social relations characterised by love and giving between spouses, parents, and children, as well as compatibility between parents and children through a relationship of love and respect, and compatibility between children and each other through the prevalence of relations of love, tolerance, cooperation, nonquarrel and self-love, so tension and poor compatibility prevail (Muhammad; Al-Zuhri; Ali, 2022). With regard to the explanation of the variation of arithmetic averages of the behaviour of consumption boasting of the desire to resort to low or moderate consumption behaviour due to the pressures of life and the financial challenges that families are currently experiencing that make them refuse to acquire luxury goods and distance from the manifestations of the ostentatious consumption pattern, this result differs to that due to the difference in the culture of consumption than it was in the past, whereby the rational simple consumer is replaced by a more complex consumer due to the increasing importance of self-images and social status. The culture of consumption is arranged by personality style and self-concept. Toth (2014) indicated the role of self-concept in determining consumer behaviour and found that most preferred to have a better appearance and self-satisfaction through consumer entertainment products. Al-Zahrani (2017) stated that the consumption pattern in the Kingdom in general tends towards luxury, as society tends to consume what is necessary and unnecessary in all directions.

Kishk (2018) reported the emergence of some manifestations of class disparity between different social strata and extravagance in occasions and others. This may be due to the large number of family requirements and burdens, the high living and the lack of income that working women need to rationalise consumption.

The differences in the study variables (personality type) due to age in favour of the group aged from 25 to less than 30 years, followed by the age group from 30 to less than 35 years are explained by the fact that the personality style is affected by these age groups. The personality differences are due to the number of children for the pattern of the thinker/sentimental, who always analyses the data and information, is characterised by kindness and compassion for those categories of children and always seeks to find positive relationships with them. With regard to the interpretation of differences according to economic income, it can be said that the personality type is affected by the level of low income, except for the type of thinker/sentimental who always seeks to resolve their problems. As for the differences in the personality pattern according to marriage duration, the shorter the duration of marriage (up to ten years), the more that period is dominated by empathy, harmony and the desire to establish positive relationships, which distinguishes a thinker/emotional pattern.

The differences in family compatibility can be explained according to age and the need of all participants without considering the age groups for family stability, and the number of family children explains that the increased number of children affects family cohesion. The duration of marriage can be explained by the existence of a positive relationship between the length of the marriage and the emergence of some family problems that may affect the nature of stability. Globalisation has affected the emergence of new values far from the nature of traditional family life, which has led to a threat to the authentic value system and formed a kind of cultural duality that combines tradition and modernity and created an intellectual and ideological conflict that affected the structure, cohesion and compatibility of the family (Al-Maliki, 2020). This indicates that the economic level does not affect the nature of stability, a result that cannot be relied upon at all because the low economic level affects the family and its ability to spend. Moreover, there is a slight effect of the wife's income on marital instability and this varies according to the husband's characteristics, such as the husband's irritability and his ability to control, and the burden of roles borne by the working wife compared to the non-working wife due to the husband's lack of cooperation and adherence to his traditional role of working outside the home only (Starkey, 1991). This indicates the conviction of the participants that the educational level does not affect family stability and some other variables and factors affect the nature of stability especially those related to personality styles, as both Brown and Brown (2002) pointed out. Family compatibility is greatly affected by the personality of the spouses, either by strengthening family compatibility or in the emergence of family disputes, due to the difference of both spouses from each other in characteristics, traits, personality style, as well as in physical and emotional composition; this difference may lead to negative effects that reflect on family compatibility.

The differences in the behaviour of ostentatious consumption among Saudi women can be explained according to work due to the impact of globalisation and its tools such as advertising on those age groups, as luxury consumption is more affected by advertisements that promote a culture of boasting and simulation (Al-Rashoud, 2018). The differences according to the number of children in the measure of boastful consumption behaviour can be explained by the phenotypic consumption that may exist in families that have a few or many children and that it is a phenomenon that families may suffer from without considering the number of children. It is known that increasing the number of children requires working women to rationalise their consumption as indicated by the study of Al-Khamshi (2017). Finally, the level of economic income in the measure of consumption behaviour boasting, in other words, low or high income influences women's behaviour towards phenotypic consumption contrary to the expectation that high-income people tend to consume appearance, studies have indicated an increased tendency to consume luxury goods (Bögenhold & Naz, 2018). It is no longer a phenomenon characteristic of the upper classes and the wealthy in society, rather, it has now included the low-income (Memushi, 2013). This has resulted in measuring the level of the individual socially as much as their consumption of goods and services, even if they are not useful.

With regard to the possibility of predicting family compatibility and ostentatious consumption behaviour through personality type. It can be explained that a thinker/emotional pattern is higher related to family compatibility because working women with this personality type are more keen on family stability. The individual with a preference for the thinking personality is characterised by the fact that they always analyse the data and information, searching for the causes and influences that may affect their judgment logically. They also seek to solve problems and difficulties logically and analytically to find an objective criterion for similar cases. The individual with an emotional personality type is also characterised by being sympathetic to others, seeking to achieve harmony, positive relationships with others, compassion and compassion for others, and justice because they want to be treated by others as an individual in society (Tashtoush, 2022; Al-Hawari, 2017; Al-Sharif, Al-Sharifeen & Al-Daqs, 2012).

Limitations

The application of the current study was limited to a random sample of Saudi women in the city of Riyadh who were selected through an electronic link according to several demographic variables. The study results were limited to three tools: 1. personality style scale; 2. the measure of ostentatious consumption behaviour; 3. the measure of family compatibility, so the generalisation of the results is determined by the extent of their honesty and stability.

Recommendations

1. Raising the awareness of Saudi women about the importance of maintaining family stability by adopting moderate consumption behaviour patterns that avoid boasting, as the study results showed that it is influenced by personality styles.

2. Paying attention to studying the personality patterns of Saudi women on an ongoing basis and educating them to follow personal patterns that maintain family stability and avoid some patterns of ostentatious consumption behaviour.

3. Conduct more comparative studies on the same variables in men and women or across different cultures.

References

Abu Nab, E. (2019). “Women’s fashion consumption in Saudi Arabia”. PhD. Thesis. De Montfort University. Leicester.

Al-Rashoud, S; Nafie, Saeed A; & Abu Farraj, A (2018). The culture of consumption among the Saudi family (a field study). Arab Journal of Educational and Social Studies. (12), 53-164.

Al-Zahrani, N (2017). The Saudi family's achievement of the concept of sustainable consumption: a field study applied to a sample of Saudi families. um Al-Qura University Journal of Social Sciences. 10(1): 117-199.

Bahauddin, F. (2020). The personality traits of the head of household and their relationship to consumer behavior, Egyptian Journal of Specialized Studies, 8(26), 19-68.

Bani-Rshaid, A. & Alghraibeh, A.(2017). Relationship between compulsive buying and depressive symptoms among males and females. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, 14, 47-50.

Bögenhold, D. & Naz, F. (2018). Consumption and life-styles: A short introduction. Palgrave Macmillan. Cham.

Brown, J. & Brown, C. (2002). Marital therapy: Concepts and skills for affective practice. Thomson learning: books/cole.

Bukhari, A (2021). Phenotypic Consumption of Luxury Goods in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: An Applied Study on the City of Jeddah, Journal of Economic, Administrative and Legal Sciences, National Research Center, Gaza, 1-24.

Chaudhuri, H. & Majumdar, S. (2010). Conspicuous consumption: Is that all bad? Investigating the alternative paradigm. Vikalpa. 35 (4): 53-59.

Cohen, Y., Ornoy, H., & Keren, B. (2013). MBTI personality types of project managers and their success: A field survey. Project Management Journal, 44(3), 78-87.

Decimal pointing. (2018). Returning migration and the transformation of consumption patterns among the middle class segments, "A field study in Tanta City", Journal of the Faculty of Arts, Faculty of Arts, Alexandria University, 68(94), 1-47.

Dialogist, S. (2017). Predictive ability of the degree of similarity in personality traits and forms of communication between spouses in family compatibility among a sample of couples, Master Thesis, Yarmouk University, Faculty of Education, Jordan, 1-149.

Good, N. (2022). Personality styles as a mediating variable in the relationship between quality of career life and ethical behavior: An applied study on employees of the General Authority for Educational Buildings, Scientific Journal of Economics and Trade, Ain Shams University, Faculty of Business, (4), 409-438.

Jain, A. & Sharma, R. (2018). Understanding of the term conspicuous consumption: A literature review. International Journal of Management and Applied Science. 4 (1): 33-34.

Khalifa, M.(2018). Identifying the personality pattern prevailing among male and female students in the two faculties of education in the State of Kuwait, Journal of the Faculty of Education, Tanta University, Faculty of Education, 69(1), 314-343.

Khamshi, J (2017). Raising the awareness of Saudi women in rationalizing spending and developing savings methods. Conference on Enhancing the Role of Saudi Women in Community Development in Light of the Kingdom's Vision 2030. 24-25 ABrill. Riyadh.

Kiosk, T. (2018). E-shopping and its role in spreading the culture of consumption: a descriptive study applied in the port city, Journal of the Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Suez Canal University, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Egypt, (25), 68-121.

Klabi, F. (2020). To what extent do conspicuous consumption and status consumption reinforce the effect of self-image congruence on emotional brand attachment? Evidence from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Journal of Marketing Analytics. 8: 99-117.

Lixăndroiu, R., Cazan, A. M., & Maican, C. (2021). An analysis of the impact of personality traits towards augmented reality in online shopping. Symmetry, 13(3), 416.

Malki, R. (2020).The Impact of Entertainment on the Value System of the Saudi Family: A Field Study on Some Families of Jeddah City, International Journal of Educational and Psychological Sciences, (54), 107-177.

Memushi, A. (2013). Conspicuous Consumption of luxury goods: Literature review of theoretical and empirical evidences. International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research. 4 (12): 250-255.

Muhammad, A; Al-Zuhri, F; Ali, S. (2022). Women's Life Management Skills and Their Relationship to Family Compatibility, Southern Dialogue journal, Assiut University, Faculty of Specific Education, (14), April, 125-173.

Rabee, M(2013). Personal Psychology, Amman: Dar Al- Masirah.

Roy Chaudhuri, H., Mazumdar, S., & Ghoshal, A. (2011). Conspicuous consumption orientation: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. Journal of Consumer Behavior, 10(4), 216-224.

Sahaf, I. (2015). Marital compatibility and its relationship to family stability among a sample of married couples in the city of Makkah, unpublished master's thesis, College of Education, Department of Psychology, um Al-Qura University, Saudi Arabia.

Sarah. S (2016). Compulsive Purchase and its Relationship to Self-Esteem among a Sample of University Students, Journal of Arab Studies, Egyptian Association of Psychologists, Egypt, 15(1-19).

Sharifeen, A; (201)8). Building a Personality Patterns Scale According to Yoon G's Theory, Journal of Educational and Psychological Sciences, University of Bahrain-Scientific Publishing Center, 19(4), 315-354.

Starkey, J. L. (1991). Wives' earnings and marital instability: Another look at the independence effect. The Social Science Journal, 28(4), 501-521.

Tashtosh, R. (2022). Personality Patterns and their Relationship to Decision Making among Educational Counselors in Jordan, Mutah Journal for Research and Studies, Humanitises and Social Sciences Series, Mutah University, 37(4), 137-176.

Toth,M.( 2014). the role of self –concept in consumer behavior,A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts - Journalism and Media Studies, Hank Greenspun School of Journalism and Media Studies, Greenspun College of Urban Affairs. The Graduate College, University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Truong, Y.; Simmons, G.; McColl, R.; & Kitchen, P. (2018). Status and Conspicuousness -Are they related? Strategic marketing implications for luxury brands. Journal of Strategic Marketing. 16 (3): 189-203.

Wang, J. & Foosiri, P. (2018). Factors related to consumer behavior on luxury goods purchasing in China. UTCC International Journal of Business and Economics. 10 (1): 19-36.

Wood, S. (2012). Prone to progress: Using personality to identify supporters of innovative social entrepreneurship. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 31(1), 129-141.

World Gold Council. (2019) . Gold demand trends full year and Q4 2019”. Available from; https://www.gold.org/ goldhub /research/gold-demand-trends.

Yusuf, G. O., Sukati, I., & Andenyang, I. (2016). Internal marketing practices and customer orientation of employees in Nigeria banking sector. International review of management and marketing, 6(4), 217-223.

Zhang, C., Brook, J. S., Leukefeld, C. G., De La Rosa, M., & Brook, D. W. (2017). Compulsive buying and quality of life: An estimate of the monetary cost of compulsive buying among adults in early midlife. Psychiatry research, 252, 208-214.

Zoukar, Z (2013). Introduction to Personal psychology and mental health, 1st ed., Markaz aleshaa alfekri for Studies and Research, Palestine,