Research Article - (2024) Volume 19, Issue 1

SPORT COACH EDUCATION PROGRAMS: PERSPECTIVES AND FEATURES

Zsolt Nemeth1, Abdumalik Shopulatov2, Hanno Felder3, Mochamad Ridwan4, Azadeh Sobhkhiz5, Mohd Asmadzy Bin Ahmad Basra6, Edi Setiawan7, Akram Abdulakhatov8 and Farruh Ahmedov9**Correspondence: Farruh Ahmedov, Retraining and Advanced Training Institute in Physical Education and Sports, Samarkand State University, Uzbekistan, Email:

2Uzbek State University of Physical Education and Sports, Uzbekistan

3Olympic Training Center, Department of Biomechanics and Sports Sciences, Germany

4Faculty of Sports and Health Sciences, Universitas Negeri Surabaya, Indonesia

5Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Iran

6Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM) Sarawak Branch, Malaysia

7Chirchik State Pedagogical Institute,Chirchik city, Uzbekistan

8Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, Universitas Suryakancana, Indonesia

9Retraining and Advanced Training Institute in Physical Education and Sports, Samarkand State University, Uzbekistan

Received: 20-Jan-2024 Published: 15-Feb-2024

Abstract

The evolution of sports coach education programs on a global scale is a dynamic and ever-improving process. This study aimed to scrutinize the characteristics, overarching development trends, and structure and content of sports coach education programs. The research involved 46 experts, each with a minimum of 8 years of coaching experience across 12 diverse sports, who participated in a comprehensive survey. Information retrieval relied on specialized scientific databases, utilizing keywords such as "coaching," "sport coaches," "program," and "education program." A total of 4539 publications were identified, with 501 selected for inclusion in this research. The study's findings reveal discernible variations in the global practice of training sports coaches, encompassing differences in program structure, content, duration, and qualification evaluation criteria. Despite these differences, a common thread unites sports coaching education programs worldwide, reflecting shared features, structures, and content. The field has matured into a prestigious domain with recognized importance in the social, scientific, and academic spheres. These results offer valuable insights for the development and effective implementation of sports coach training programs, contributing to the ongoing refinement of coaching practices globally

Keywords

Coaching. Education programs.Certification. Qualification. Features

Introduction

Sports coach education programmes (CEPs) exhibit diverse implementations across different countries and are often shaped by distinct approaches and frameworks. These programs find their primary deployment within specific universities and institutions, often in collaboration with national sports federations. While notable strides have been made, particularly in countries such as the UK and Canada, focusing on the development, effective implementation, and consistent delivery of CEPs, the global landscape reveals a significant departure from this trend (Lyle et al., 2010). Countries worldwide demonstrate varying practices in the training of coaches, highlighting the need for a comprehensive understanding of the existing disparities. Notably, efforts in nations such as the UK and Canada underscore the importance of shaping CEPs through collaborative initiatives involving educational institutions and sports federations. However, practices in other parts of the world deviate from this established trend, suggesting a dynamic and evolving global scenario in sports coach education. In recent decades, there has been a shift in focus within coach education, placing increased emphasis on interpersonal relationships, personal behavior management (Evans et al., 2015; Langan et al., 2013), general curricular features (Trudel et al., 2020), and contemporary issues in coach education (Callary et al., 2014). Despite these advancements, there remains a noticeable gap in research examining the future trajectory and specific aspects of coach education programs. This study aims to contribute to filling this gap by providing a comprehensive analysis of the current global landscape of coach education programs. By exploring the diversity of CEPs worldwide, we seek to draw conclusions about their effectiveness and inform the development of optimal approaches in the future. Understanding the unique features and challenges of coach education programs globally is imperative for fostering continuous improvement and enhancing the overall quality of sports coaching.

Sports coach education programmes (CEPs) play a pivotal role in elevating the status of the coaching profession within society. The cultivation of coaches armed with profound knowledge and critical thinking skills have significant social implications, extending beyond the confines of the sports industry to impact society at large (Armour, 2010). Proposals advocating for enhancements in training programs, including the development of alternative educational approaches to CEPs and the integration of theory and practice, have advanced (Cushion et al., 2003). However, the practical implementation and effectiveness of such proposed approaches lack accurate data and empirical scrutiny. The synergy between theory and practice in coach education programs is critical for producing well-rounded and highly competent coaches. The gap between the proposed improvements and their actual incorporation into CEPs underscores the need for a scientific analysis of the content, structure, and features of coach training programs. Such an analysis is crucial for evaluating the efficacy of existing programs and identifying areas for enhancement. In essence, the modernization of sports education hinges on a thorough understanding of the dynamics of coach education programs. The alignment of these programs with contemporary educational needs not only enhances the quality of coaching but also contributes to the broader societal understanding of the coaching profession. By delving into the intricacies of CEPs, this study aims to shed light on their content, structure, and features, providing valuable insights for the ongoing evolution of sports education. This research endeavors to bridge the gap between theoretical proposals and practical implementation, fostering a more effective and impactful sports coaching landscape.

In the current international community, the refinement of sports coach training practices is acknowledged, but scholars such as Taylor & Garrett (2013) assert that traditional educational formats may fall short in ensuring the development of coaches' expertise in modern sports practices. This perspective suggests that relying solely on conventional teaching methods may not adequately equip coaches for the dynamic challenges of contemporary sports coaching. Trudel et al. (2013), advocate for a departure from the historically traditional and widely accepted characteristics of educational programs. They argue that training programs for coaches must evolve to provide the knowledge and skills requisite for their professional roles. This implies a need for a shift away from conventional approaches and a move toward more innovative and contemporary methods in coach education. While the significance of curriculum content in coach training programs is paramount, Trudel et al. (2010) caution against assuming that the entirety of the content taught is effectively absorbed by future coaches. The degree of successful transmission and absorption of educational content has become a critical factor in evaluating the overall effectiveness of coach education programs. Simply imparting information does not guarantee comprehensive assimilation, prompting a re-evaluation of the teaching methodologies employed. In essence, the challenge lies in not only delivering information but also ensuring its meaningful uptake and application. The evolving landscape of sports coaching demands a shift toward more dynamic, engaging, and effective teaching methods to bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical competence. This study aimed to explore these dynamics further, shedding light on the nuances of coach education programs and proposing ways to enhance their effectiveness in preparing coaches for the demands of modern sports practice.

The global reviews conducted by the International Council for Coaching Excellence (ICCE) and the Association of Summer Olympic International Federations (ASOIF) in 2013 highlight a deficiency in training programs worldwide for highly professional sports coaches. This scarcity underscores the need for more comprehensive and diverse teaching methods in the education of trainers, with an emphasis on advanced approaches. Despite the recognition of this need, a discernible gap persists between the current state of coach training and coaching practices, indicating a lack of continuity between theory and practical application in this domain. While some progress has been made in coach training, as noted by Callary et al. (2014), the presence of conflicting opinions in the scientific literature accentuates the complexity of the issue. The varied perspectives and opinions on coach training suggest that there is no singular, universally accepted format for addressing this challenge. Moreover, the limited availability of information on the analysis of sports coach training practices at the international level hampers the identification of optimal training programs that could serve as a model for others.

In light of these considerations, this research undertaking aims to address two parallel objectives:

I) to delve into the intricacies of the experience of training sports coaches at the international level, seeking to uncover the specific nuances and challenges encountered in this process.

II) To conduct a comparative analysis of global trends, structures, and content within sports coach training programs.

This analysis provides insights into the existing diversity and variations in coach education practices globally.

The importance of this research lies in its potential to significantly enhance the landscape of coach education programs. By uncovering valuable insights into the dynamics of coaching effectiveness and identifying key factors that contribute to successful coaching, this study becomes a cornerstone for the development of future coach education initiatives. Coaches and program developers can leverage these research findings to fine-tune existing curricula, design targeted training modules, and implement evidence-based practices. Ultimately, this research not only advances our understanding of effective coaching but also empowers the sports community to nurture and cultivate a new generation of skilled and impactful coaches.

This research holds significant importance due to its scientific novelty and the depth of insights it offers. By synthesizing findings from numerous best practices and drawing on the experiences of leading countries in sports coach training programs, it elevates the field by providing evidence-based conclusions and perspective insights. This not only adds to the body of scientific knowledge but also serves as a comprehensive resource for shaping future strategies in coach education. The incorporation of diverse international perspectives and proven methodologies enhances the credibility and applicability of the research, making it a valuable guide for global advancements in sports coaching education.

By pursuing these objectives, this research seeks to contribute to the understanding of the complexities surrounding sports coach training at an international level. The findings could offer valuable insights for the development of more effective and standardized training programs, bridging the gap between theory and practice in the education of sports coaches.

Methods

Choosing a Topic

The selection of the research topic was initiated by the Samarkand branch of the Institute of Retraining and Qualification of Sports Specialists under the Ministry of Sports of the Republic of Uzbekistan. The aim was to investigate the global experience of training, organizing, and educating sports coaches. The authors of the research paper presented the chosen topic to 46 specialists in physical education and sports employed in educational institutions. To assess the relevance and importance of the proposed topic, participants were asked to indicate their agreement or disagreement.

Participants

The survey involved specialists with a background in physical education and sports, who possessed higher education credentials and a minimum of 8 years of work experience in the field. The average age of the participants was 45±8.1 years, and their cumulative work experience averaged 18±4.3 years. The sports specialties of the coaches included football (6), volleyball (4), basketball (4), athletics (8), kurash (6), table tennis (4), tennis (3), gymnastics (3), judo (3), fencing (1), archery (2), and swimming (1). All participants in the survey unanimously affirmed the relevance of the chosen topic, as indicated in (Table 1).

| N0. | Sport Specialization | Number | Agree | Disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Football | 6 | + | - |

| 2. | Volleyball | 4 | + | - |

| 3. | Basketball | 4 | + | - |

| 4. | Track and Field Athletics | 8 | + | - |

| 5. | Kurash | 6 | + | - |

| 6. | Table Tennis | 4 | + | - |

| 7. | Tennis | 3 | + | - |

| 8. | Gymnastics | 3 | + | - |

| 9. | Judo | 3 | + | - |

| 10. | Fencing | 1 | + | - |

| 11. | Archery | 2 | + | - |

| 12. | Swimming | 1 | + | - |

| Total | 46 | 100% | - | |

This table summarizes participants' agreement on the relevance of the chosen research topic, organized by their respective sports specializations. The "Agree" column indicates whether participants agreed with the relevance of the chosen topic, and the "Disagree" column denotes whether participants disagreed. All participants agreed on the significance of the chosen research topic across different sports specializations.

Literature Search Strategy

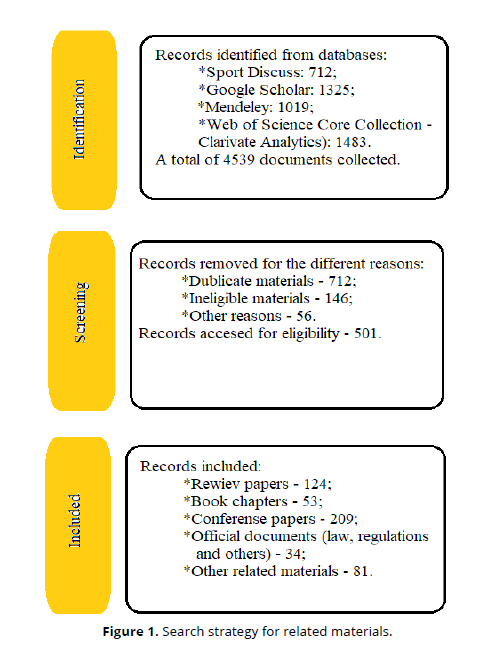

The literature searching for this study comprised three interconnected phases: identification, screening, and inclusion. The research sources were primarily accessed at the library of Samarkand State University, and the literature examined was in English. The search utilized the following keywords: "COACHING", "SPORT COACHES", "PROGRAM", and "EDUCATION PROGRAM". The distribution of searchable research data across various scientific platforms is outlined below:

- Sport Discuss: 712

- Google Scholar: 1325

- Mendeley: 1019

- Web of Science Core Collection (Clarivate Analytics): 1483

The aggregate number of sources identified across all platforms was 4,539. Following a meticulous review, materials unrelated to the research topic and duplicate content were excluded from the general list. The final analysis resulted in a refined collection of 1,415 publications. From this subset, 501 publications were selected for inclusion and utilization in the research (Figure 1).

Figure 1 visually represents the literature search process, illustrating the refinement from the initial identification phase to the final inclusion of 501 relevant publications after the screening and elimination of irrelevant or duplicate materials. This comprehensive approach ensured the selection of high-quality and pertinent literature for the research study.

Screening and Classification

The sources constituting the research object underwent a thorough examination by the scientific group based on the following specified criteria:

Inclusion criteria

1. The publications aimed to describe and analyse sports coaching programs.

2. Policies and documents on the training of sports coaches developed by the government.

3. Publications on the certification policy and qualification levels of sports coaches

Exclusion criteria

1. Publications not related to the training of sports coaches.

2. Materials concerning the certification of sports coaches that are not pertinent to determining their qualification level.

The research team conducted a comprehensive reanalysis of the collected publications, and those that did not align with the stipulated conditions of the study were systematically excluded from the list. This rigorous screening process ensured that only relevant and pertinent materials were retained for further analysis and integration into the research.

Results

Description of Coach Education Programs

The Botswana National Olympic Committee has emerged as a prominent entity in the training and accreditation of sports coaches within the country, showcasing a robust long-term training program for coaches (Tshube & Hanrahan, 2018; Moustakas & Tshube, 2020). This comprehensive programme encompasses three primary directions:

(a) Junior Coaches/Coaches for Junior Classes: Coaches in this category are tasked with developing the fundamental physical movement skills and basic sports exercises of children.

b) Coaches for Secondary School Students: This segment of the program focuses on evaluating the athletic abilities of children and enhancing their competitive experiences.

(c) Coaches of the Highest Sports Achievements at the Post-High School Level: Designed for coaches overseeing athletes at the pinnacle of sports achievements beyond the high school level.

Notably, there are no specified academic requirements for sports coaches in Botswana. Instead, coaches are required to undergo a series of training courses, each building upon the previous level:

Level 1: A two-week course followed by an examination.

Level 2: Involves mentorship and the creation of a portfolio containing training schedules and other materials to enhance coaching skills.

Level 3: A continuation of the training with an additional examination.

Level 4: Requires practical work and the development of a portfolio.

This structured progression through different levels ensures a comprehensive and practical approach to coach education in Botswana. The emphasis on mentorship and practical experience, as evidenced by portfolio requirements, aligns with contemporary approaches to sports coaching education (Tshube & Hanrahan, 2018; Moustakas & Tshube, 2020).

In Ireland, sports coach training programmes reflect a blended approach, adhering to regulations set by the United Kingdom, Northern Ireland, and the Republic of Ireland. The foundation for the training of sports coaches and their professional development in Ireland is based on the "4 by 4 Coach Education Model-CEM," which encompasses the following categories:

(a) Children’s Coach; (b) Participation Coach; (c) Performance Coach; (d) High- Level Coach.

In the context of football, a well-established sport in Ireland, governance is divided between the Irish Football Association (IFA) for Northern Ireland and The Football Association of Ireland (FIA) for Southern Ireland (Chambers & Gregg, 2016). The FIA's Coach Training Program incorporates four distinct license types, with mandatory coaching courses in children's football for all candidates participating in coaching courses (O’Regan and Kelly, 2018). The license categories and qualification requirements for coaches under the FIA are delineated as follows:

1. Grassroots Football: Kick Star-1 and Kick Star-2.

2. Adult Football: D and C National License: UEFA-B (120-hour course); UEFA-A (minimum 180-hour course); UEFA-A Elite Youth (minimum 80-hour course); UEFA-A Combined Elite Youth (minimum 260 hours); UEFA-PRO (minimum 360 hours).

3. Futsal: D and C Licenses: UEFA-B (minimum 120-hour course).

4. Goalkeeper: D, C, and B Licenses; UEFA A GK (minimum 120 hours). The attainment of all licenses is contingent on practical experience, with coaches evaluating various criteria, including individual performance, correction in the position of natural stop, manipulation and imitation of movements, video analysis, and description of game situations, self-study, coaching style, coaching philosophy, and game evaluation. This multifaceted assessment ensures that coaches undergo a holistic evaluation, aligning with contemporary coaching methodologies and emphasizing practical competence (O’Regan & Kelly, 2018).

In Brazil, the training of sports coaches is deeply rooted in tradition and is continually evolving to align with modern trends. A key prerequisite for individuals aspiring to become sports coaches in Brazil is the possession of a university degree, specifically a bachelor's degree, in the field of "physical education". However, football, which is a particularly significant sport in Brazil, has distinct requirements, and candidates for football coaching roles do not necessarily need a diploma in physical education (Milistetd et al., 2014; Novais et al., 2021).

Brazil offers four levels of coaching for football, each with specific requirements

(a) Level Pro: Completion of 320-240 hours of training (30 hours of supervision, 30 hours of assessments).

(b) License A: Completion of 210-140 hours of training (40 hours of supervision, 30 hours of assessments).

(c) License B: Completion of 180-140 hours of training (30 hours of supervision, 20 hours of assessments).

(d) License C: Completion of 150-90 hours of training (30 hours of supervision, 20 hours of assessments).

Each level of the coaching course is designed with specific tasks and goals, creating an interconnected and continuous system that caters to the different skills and experiences of trainers. Notably, the Brazilian Olympic Committee (Comite Olimpico Brasileiro) plays a central role in the training of sports coaches in the country. This emphasizes the significance of a centralized governing body in shaping and guiding coach education initiatives in Brazil.

In Finland, the Finnish Olympic Committee (FOC) serves as the governing body regulating the development and implementation of training programs for all organizations specializing in coach education within the country (Kaisa- Mari Jama et al., 2023). This inclusive system encompasses national sports federations, institutes, universities, sports academies, and research centers. The Coach Education Pathway in Finland is structured into three primary directions:

(a) Training Programs of Sports Federations: This direction likely focuses on specialized coaching programs developed and delivered by national sports federations.

(b) Vocational Coach Education Program (VCEP): This program is designed to provide vocational-level coach education, catering to the practical aspects and skills needed in coaching.

(c) High Education Coach Education Programs: This direction involves training programs for trainers at universities and institutes, emphasizing a higher educational level in coach education.

The national model for coach training in Finland establishes specific requirements for the competence of candidates, with titles awarded based on the skills and qualifications of the coaches. The coach education pathway is structured into three levels, each corresponding to distinct competencies.

1. Level 1: Candidates at this level should demonstrate competence in organizing individual training sessions.

2. Level 2: Competence at this level includes planning, organizing, evaluating, and analyzing the annual training system.

3. Level 3: Coaches at this level are expected to have the competence to plan and implement a long-term training system for athletes (Hämäläinen and Blomqvist, 2016).

This competency-based approach aligns with the evolving landscape of coach education, emphasizing the development of practical skills and longterm planning strategies for coaches in Finland. The involvement of various institutions and a clear progression pathway further strengthens the coach education system in the country.

The Netherlands stands out as a global leader in athlete training, offering coaching programs through universities and national sports federations. One distinctive program in the country is the Top Coach 5, as described by Ooms et al. (2019), De Bosscher et al. (2008).

The Top Coach 5 program in the Netherlands comprises several stages:

1. Secondary Education – Level 1: This likely represents an introductory stage in coach education at the secondary education level.

2. Vocational Education – Levels 2, 3, and 4: These levels likely encompass progressively advanced vocational coach education.

3. High Education – Level 5: Level 5 indicates the highest tier of coach education, likely offered at the higher education level.

The Top Coach 5 program is unique globally and is organized through collaboration among the National Olympic Committee of the Netherlands, sports federations, and universities. This competitive program focuses on developing competencies, knowledge, and skills in candidates (van Klooster & Roemers, 2011).

The program entails a total of 2,100 hours, emphasizing various requirements for future coaches:

(a) Knowledge: Developing candidates' perspectives, views, and approaches to the field.

(b) Skills: Increasing candidates' practical experience through participation in guided practical classes led by experienced trainers.

(c) Attitudes: Developing interview skills during candidates' work and fostering video analysis skills.

(d) Personal Characteristics: Cultivating qualities not specific to a particular sport. This involves working with candidates on the development of personal qualities over a duration of 8-24 months.

(e) Assessment: Evaluating the acquired knowledge of each candidate through testing in their chosen field.

This holistic approach, which incorporates knowledge, skills, attitudes, personal characteristics, and assessment, reflects the comprehensive and competitive nature of the Top Coach 5 program in the Netherlands. This study underscores the importance of practical experience and the development of a well-rounded skill set for coaches in the country.

Australia, recognized as a global sports powerhouse, places significant emphasis on coach education, particularly in sports such as Track and Field Athletics. The Australian Track and Field Coach Accreditation program, initiated in 1974, has been pivotal in shaping the coaching landscape. The program has evolved, and since 2016, it has been organized into five interrelated stages, as outlined by the Australian Track & Field Coaches Association (2015).

1. Introduction to the Coaching Course: An 8-hour training course designed for candidates with low or insufficient qualifications.

2. Foundation Course: A 16 hours training course was tailored for young sports coaches, and a control test was administered at the end of the course.

3. Event Group Specialists Course: A 14 hours training course catering to coaches specializing in specific competitions or training. This course includes a face-to-face practical test at its conclusion.

4. Elite Performance Course: A comprehensive 4 days training program accompanied by a practical knowledge test.

5. Master: Involves participation in professional development programs over 24 months, along with verification of theoretical and practical knowledge, including video analysis.

This structured coaching programme addresses the varying needs and qualifications of coaches at different stages of their careers. The focus on practical assessments and ongoing professional development aligns with contemporary coaching methodologies.

Recent improvements in the Australian sports coaching programme, especially in the context of Track and Field Athletics, have prioritized the professional training of young and inexperienced coaches (Moore et al., 2022; Wareham et al., 2018). This reflects a commitment to staying current with evolving coaching practices and ensuring the continuous improvement of coach education in Australia.

In Spain, training programs for sports coaches, coupled with the legal framework, have undergone continuous improvement. In 1994, the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science (MEC-Royal Decree 594/1994) established qualification requirements for sports coaches, marking a significant milestone in enhancing the coach training system in the country and aligning educational programs with international standards. As outlined in Royal Decree 594/1994, Spain has clear and specific requirements for sports coaches at different levels:

1. Elementary Sport Technician: Candidates must be at least 18 years old and possess a high school diploma.

2. Basic Sport Technician: Candidates are required to complete a 200 hours refresher course or participate in an Elementary Sport Technician program during one academic season.

3. High Sport Technician: Candidates need to complete a 200 hours refresher course or participate in a Basic Sport Technician program during one academic season.

Interestingly, the coaching community in Spain places a strong emphasis on continuous improvement and the development of high-quality training programs (Feu et al., 2018). The commitment to improvement is reflected in the frequent updates to official documents on physical education and sports, with nine revisions between 1980 and 2013, most of which include provisions on the training of sports coaches. However, the changes and improvements made to training programs in recent years have presented challenges for candidates. The notable increase in training time underscores the necessity for sports coaches to adapt to evolving processes (Spanish Government, 1998).This highlights a commitment to maintaining high standards and ensuring that sports coaches are well equipped to meet the demands of contemporary coaching practices in Spain.

China, as a prominent force in international sports, has placed significant emphasis on the training of sports coaches, particularly within the higher education system. According to analytical sources (Chen & Chen, 2022; Ji et al., 2021), the Chinese government has been consistently enhancing legislation and the system for training highly qualified sports coaches. This dedication has translated into notable success at international sports competitions, particularly at the Olympic Games. The key points regarding sports coach training in China include the following:

1. University-based training: The primary avenue for sports coach training in China is through universities within the higher education system.

2. Government Support: The Chinese Department of Education actively supports the participation of university students in international sports competitions, fostering a holistic approach to coach development.

3. Leading Institution: Beijing Sports University (BSU) holds a prominent position in the training of sports coaches and the implementation of educational programs in China. The 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing triggered significant changes in coaching practices and methodologies within the country (Liu, 2016).

4. High Competency Levels: China's experience demonstrates that the basic competencies of sports coaches are high. In 2004, Beijing Sports University (BSU) played a pivotal role in developing training programs for highly qualified sports coaches, with the Guangzhou Physical Education Institute introducing special courses in 2005 (Li & Zhao, 2013).

5. Systematic Policies and Improvements: Systematic policies and continuous improvements in sports coach training have elevated China to one of the highest levels globally. The concerted efforts in legislation, educational programs, and practical training have contributed to China's success in producing highly qualified sports coaches.

China's commitment to the ongoing improvement of sports coach training reflects its strategic approach to maintaining excellence in international sports competitions. With the combination of institutional support, government initiatives, and systematic improvements, China is positioned as a leader in the field of sports coach education.

South Korea holds a significant and progressing position in the global landscape of training sports coaches, with notable developments and a positive trend (Nasir et al., 2022; Park, 2007).

The key aspects of sports coach training in South Korea include the following:

1. University Leadership: Universities play a leading role in the training of sports coaches in South Korea. The collaboration between universities and national sports federations is well established.

2. Establishment of the Korea Coach Association: In 2012, the Korea Coach Association was established, signifying a concerted effort to organize and streamline sports coach training in the country.

3. Training Programs and Certification: The Korea Coach Association offers a comprehensive range of sports coaching programs, total of 106. These programs contribute to improving the skills and knowledge of sports coaches in South Korea. Additionally, coaching certificates are issued by more than 60 organizations, indicating a broad network of recognition and certification within the coaching community.

The collaboration between educational institutions and sports organizations, as well as the establishment of dedicated associations such as the Korea Coach Association, showcases South Korea's commitment to providing a structured and extensive framework for sports coach education. The availability of numerous coaching programmes and widespread certification reflects a holistic approach to developing skilled and knowledgeable sports coaches in the country.

Japan has developed a distinctive and high-quality training system for sports coaches characterized by its collaboration with key entities such as the Japan Sport Association, national federations, universities, and the Japanese Olympic Committee. The qualifications of sports coaches in Japan are organized into five sectors, reflecting a tiered system from lower to higher levels.

The key features of sports coach training in Japan include the following:

1. Collaboration with Key Organizations: The training of sports coaches involves collaborative efforts with the Japan Sport Association, national federations, universities, and the Japanese Olympic Committee. This multi stakeholder approach ensures comprehensive and well-rounded training experience.

2. Qualification Sectors: The qualifications for sports coaches in Japan are categorized into five sectors, representing a structured progression from lower to higher levels. This tiered approach likely allows coaches to specialize and advance in their coaching careers.

3. Focus on Education and Training across Ages and Levels: The primary content of coaching courses and training programs in Japan is directed toward providing education and training for players of different ages and levels. This reflects a holistic approach to coach development, emphasizing versatility in coaching capabilities.

4. Positive Trend towards Professional Knowledge: The evolution of sports coach training in Japan has led to a positive trend toward equipping coaches with professional knowledge in a specific sport. This evolution aligns with the overarching goal of using sports as a medium for the holistic development of individuals (Miller, 2011).

The Japanese approach to sports coach education combines professionalism in specific sports with the broader concept of using sports as a means for personal development. This dual emphasis reflects a comprehensive vision for sports coaching in Japan, addressing both technical expertise and the broader educational and developmental aspects of coaching.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to analyse (I) the intricacies of the experience of training sports coaches at the international level, seeking to uncover the specific nuances and challenges encountered in this process, and (II) the comparative analysis of global trends, structures, and content within sports coach training programmes.

An analysis of the training system for sports coaches in a number of countries has confirmed that each country has its own approaches and practices for training sports coaches. These two groups differ from each other in terms of the requirements for the qualifications, competence and knowledge of the coaches. Duffy et al. (2011), noted that today, the training of sports coaches is in a stage of intensive and rapid development. However, the activity of a sports coach should determine the prospects for further development as a mixed profession, including sports and physical activity, and should be consistently integrated into the process of deep professionalization. Opinions on this matter have also been confirmed in recent studies. Analyzing training programmes for sports coaches in 26 European countries, showed that there are certain shortcomings in this process. Despite the progress made in training coaches in Europe, a number of disadvantages are also obvious (Moustakas et al. 2022). It is noteworthy that these opinions are reflected in scientific research and the conclusions of other researchers. In particular, Schulenkorf & Frawley (2016), listing the problems of modern sports, emphasize that issues of sports management, ensuring gender equality in sports, corruption in sports, and doping are important in modern sports (Schulenkorf & Frawley, 2016). Contrary to this opinion, currently, in all countries, the system of training coaches, in particular, in the content of educational programmes, does not reflect the provision of knowledge to sports coaches on the above issues.

The study showed that the practice of training sports coaches is also associated with the level of development and popularity of a particular sport in a given country. In brief, the development of a particular sport in the country is directly related to the system of training specialists in that sport. A number of studies are devoted to the development of football in European countries, its high level of popularity and the world's leading training of football specialists (Missiroli, 2002). Brand & Niemann (2014) noted that, according to the results of their study, football is an integral part of the social and cultural life of the inhabitants of Europe (Brand & Niemann 2014). The above factors directly affect the system of training football coaches and the quality of educational programs. At this stage, the conclusions we have noted above can be considered justified.

Based on our observations and research results, it should be recognized that the current trend and historical development of the practice of training sports coaches are based on a system of cooperative training. This approach has not lost its effectiveness and efficiency; it is still used in the training of sports coaches worldwide. For example, as the Hungarian experience shows, cooperation between universities, the Hungarian Olympic Committee and national sports federations is well established, and training programs for sports coaches have been established for a number of sports (Géczi et al. 2015; Perényi & Bodnár 2015). This experience can be seen in other countries worldwide. For example, training and certification programs for Portuguese sports coaches are carried out in cooperation between national sports federations and universities (Resende et al., 2016). Research in Spain notes that sports coach training programmes are inextricably linked to education and that this experience has undergone a long history of development (Feu et al. 2018). Based on the latest analysis included in the scope of the study, there is a general development and growth of the practice of training sports coaches in accordance with the global trend. According to their research, specific approaches exist in a number of European countries, particularly in Germany, Belgium, Great Britain, Estonia, France, Finland, Spain, Switzerland, Italy, Portugal and Turkey (Voicu et al., 2021). In particular, there are certain differences in course duration, qualification requirements, teacher level, knowledge assessment, course teaching and other similar aspects. Nevertheless, it is possible to identify common trends and features in the practice and theory of training sports coaches.

Another important issue to discuss is the legal basis for the training of sports coaches. Our analysis confirmed that the system of training and certification for sports coaches cannot be created without a legal basis. Accordingly, our conclusions are consistent with the results of other scientific studies. Voicu et al. (2021), expressed an opinion on the issue of the professional responsibility of sports coaches, recognizing the importance of legal norms in the organization of this activity. Importantly, opinions on this issue have been scientifically substantiated by other researchers. Wagner (2013), researched the ethical, social and legal issues of training sports coaches and showed that legal norms and legal frameworks play important roles in modern sports. According to him, it is important to have a solid legal basis and standards for the training of a morally mature and intellectually mature coach. Dieffenbach & Thompson (2020), in their opinion, it is necessary to apply a fully mature legal framework not only in the system of training sports coaches but also at all stages of the sports sphere, in particular, in the process of training athletes; in Olympic and Paralympic sports; in educational processes and training; and in the educational processes of sports coaches (Dieffenbach & Thompson, 2020). Such legal frameworks and norms are effective in the athlete training system, in regulating effective interactions between coaches and athletes, and in ensuring that coaches fully perform their duties.

Mapping the Global Landscape of Sports Coach Training

The comprehensive analysis of sports coach training practices across the globe offers valuable insights into the diverse approaches, commonalities, and emerging trends in this dynamic field. The key conclusions and reflections from the study include the following:

Global Research Landscape

An extensive literature search revealed a rich body of research dedicated to exploring the nuances of sports coach training worldwide. This signifies the global importance and scholarly interest in understanding the intricacies of coach development.

Comparative analysis insights

The comparative analysis of training programs, evaluation systems, and duration of courses showcased a spectrum of diverse approaches. These differences are rooted in varying sports policies, legal frameworks, and cultural contexts, illustrating the need for context-specific coaching education.

Common Features and Trends

Despite the diversity, common features, structures, and content were identified in sports coach training programs globally. This indicates shared principles and methodologies that transcend national boundaries, contributing to the professionalization of sports coaching.

Prestige of Sports Coaching

The recognition of sports coaching as a prestigious and esteemed profession across social, scientific, and academic domains underscores its elevated status. This finding reinforces the importance of investing in quality coach education programs.

Variability in legal frameworks

The study highlighted the influence of legal frameworks and sports policies on the variability in coach training practices. A mature legal foundation emerged as a critical factor in ensuring the ethical, moral, and professional development of coaches.

Dynamic Nature of Coach Training

The dynamic and rapidly evolving nature of sports coach training indicates a responsiveness to changing trends, technologies, and societal expectations. This adaptability is crucial for coaches to remain effective in an ever-evolving sports landscape.

Need for Contextual Sensitivity

The existence of commonalities alongside diverse approaches emphasizes the importance of contextual sensitivity in coach training. A one-size-fitsall approach may not be effective, necessitating an understanding of local contexts and needs.

Implications for Future Research

The analysis suggests avenues for future research, including a deeper exploration of the impact of cultural factors on coaching practices, the role of technology in coach education, and the effectiveness of collaborative international initiatives in advancing coach development.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the global map of sports coach training is a mosaic of diverse, shared principles, and ongoing evolution. This study contributes to the broader conversation on the professionalization of sports coaching, emphasizing the need for continued research, collaboration, and contextualized approaches to meet the evolving demands of the sports coaching profession worldwide.

The significance of this research is underscored by its tangible impact on the future of sports coach education. The results and conclusions derived from the study provide a roadmap for the purposeful and strategic development of training programs for sports coaches. This isn't just theoretical; it's a practical guide that equips educators and practitioners with actionable insights to design and implement effective coaching programs. The direct applicability of the research findings ensures that the training programs created based on this research will be tailored to address real-world challenges and foster optimal coaching skills. Ultimately, this research bridges the gap between theory and practice, contributing to the enhancement of the sports coaching profession through targeted and impactful educational initiatives.

Limitations of the Study

While this research paper provides valuable insights into the global landscape of sports coach training, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations that impact the scope and depth of the study.

Absence of On-Site Visits

The research did not involve on-site visits to different countries for a direct, firsthand examination of sports coach training practices. Conducting such visits could have enriched the study by offering in depth, real-time observations and interactions with diverse coaching programs.

Non-classification of Sports

The analysis of sports coach training programs lacked classification based on specific sports. A more granular examination, categorizing training programs according to sports type, could have provided targeted insights into the unique requirements and nuances associated with coaching in different athletic disciplines.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to the staff of the Samarkand branch of the Institute of Retraining and Advanced Training of Specialists in Physical Education and Sports of the Ministry of Sports of the Republic of Uzbekistan, who participated in the experiment.

References

Armour, K. (2010). The learning coach… the learning approach: Professional development for sports coach professionals. Sports coaching: Professionalization and practice, 153-164.

Australian Track & Field Coaches Association. 2015 Coach education programs. Mod Athl Coach Mag. October 2015:2, 43.

Brand, A., & Niemann, A. (2014). Football and national identity in Europe. Panorama: Insights into Asian and European Affairs, 1, 43-51.

Callary, B., Culver, D., Werthner, P., & Bales, J. (2014). An overview of seven national high performance coach education programs. International Sport Coaching Journal, 1(3), 152– 164. https://doi.org/10.1123/iscj.2014-0094

Chambers, F., & Gregg, R. (2016). Coaching and coach education in Ireland. International sport coaching journal, 3(1), 65-74.

Chen, X., & Chen, S. (2022). Sports Coaching Development in China: the system, challenges and opportunities. Sports Coaching Review, 11(3), 276-297.

Cushion, C. J., Armour, K. M., & Jones, R. L. (2003). Coach education and continuing professional development: Experience and learning to coach. Quest, 55(3), 215-230.

De Bosscher, V., De Knop, P., & van Bottenburg, M. (2008). Sports, culture and society: why the netherlands are successful in elite sports and belgium is not? A comparison of elite sport policies. Kinesiologia Slovenica, 14(2).

Dieffenbach, K., & Thompson, M. (Eds.). (2020). Coach education essentials. Human Kinetics Publishers.

Duffy, P., Hartley, H., Bales, J., Crespo, M., Dick, F., Vardhan, D., ... & Curado, J. (2011). Sport coaching as a ‘profession’: Challenges and future directions. International Journal of Coaching Science, 5(2), 93-123.

Evans, M. B., McGuckin, M., Gainforth, H. L., Bruner, M. W., & Côté, J. (2015). Coach development programmes to improve interpersonal coach behaviours: A systematic review using the re aim framework. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 49(13), 871–877. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-094634

Feu, S., García-Rubio, J., Antúnez, A., & Ibáñez, S. (2018). Coaching and Coach Education in Spain: A Critical Analysis of Legislative Evolution. International Sport Coaching Journal, 5(3), 281-292. https://doi.org/10.1123/iscj.2018-0055

Géczi, G., Bartha, C., Kassay, L., Sipos-Onyestyák, N., & Gulyás, E. (2015). CoaCh eduCation aPProaCh in 16 hungarian sPort federations results of the first sPort organizational audit. Applied Studies in Agribusiness and Commerce, 9(1-2), 87-91.

Hämäläinen, K., & Blomqvist, M. (2016). A New Era in Sport Organizations and Coach Development in Finland. International Sport Coaching Journal, 3(3), 332-343. Retrieved Oct 27, 2023, from https://doi.org/10.1123/iscj.2016-0075.

Langan, E., Blake, C., & Lonsdale, C. (2013). Systematic review of the effectiveness of interpersonal coach education interventions on athlete outcomes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 14(1), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.06.007.

Liu, R. (2016). Research on Sustainable Development of Competitive Sports in Universities in China. In 2016 International Conference on Education, Sports, Arts and Management Engineering (pp. 217-221). Atlantis Press.

Li, Y., & Zhao, H. (2013). Research on Training Status and Countermeasure of Strength and Conditioning Coaches in China. In 2013 International Workshop on Computer Science in Sports (pp. 110-112). Atlantis Press.

Lyle, J., Jolly, S., & North, J. (2010). The learning formats of coach education materials. International Journal of Coaching Science, 4(1). 35-48.

Milistetd, M., Trudel, P., Mesquita, I., & do Nascimento, J. V. (2014). Coaching and Coach Education in Brazil. International Sport Coaching Journal, 1(3), 165-172. Retrieved Oct 25, 2023, from https://doi.org/10.1123/iscj.2014-0103.

Miller, A. L. (2011). From Bushidō to science: A new pedagogy of sports coaching in Japan. In Japan Forum (Vol. 23, No. 3, pp. 385-406). Taylor & Francis Group.

Missiroli, A. (2002). European football cultures and their integration: the'short'Twentieth Century. Sport in Society, 5(1), 1-20.

Moustakas, L., & Tshube, T. (2020). Sport policy in Botswana. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 12(4), 731-745.

Moustakas, L., Lara-Bercial, S., North, J., & Calvo, G. (2022). Sport coaching systems in the European Union: State of the nations. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 14(1), 93-110.

Moore, M. A., Reynolds, J. F., Durand, J., Trainor, K., & Caravaglia, G. (2022). Mental health literacy of Australian youth sport coaches. Frontiers in sports and active living, 4, 871212.

Nasir, N. A., Mohd Kassim, A. F., & Zainuddin, N. F. (2022). Investigation of Coaching Effectiveness and Perfectionist in Sports: A Systematic Review. In International Conference on Movement, Health and Exercise (pp. 361-386). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

Novais, M. C. B., Mourão, L., Souza Junior, O. M. de, Monteiro, I. C., & Pires, B. A. B. (2021). Women’s football coaches and assistant coaches in brazil: subversion and resistance in sports leadership. Movimento, 27, e27023. https://doi.org/10.22456/1982-8918.106782 https://www.cob.org.br/pt/

O’Regan, N., & Kelly, S. (2018). Coaching and coach education in the football association of Ireland. International Sport Coaching Journal, 5(2), 183-191.

Ooms, L., Van Kruijsbergen, M., Collard, D., Leemrijse, C., & Veenhof, C. (2019). Sporting programs aimed at inactive population groups in the Netherlands: factors influencing their long-term sustainability in the organized sports setting. BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation, 11(1), 1-18.

Park, J. K. (2007). The Korea Coaching Development Center (KCDC): Hoping to be a role model of coaching institutions in the world. International Journal of Coaching Science, 1(2), 63-70.

Perényi, S., & Bodnár, I. (2015). Sport clubs in Hungary. Sport clubs in Europe: A cross-national comparative perspective, 221-247.

Resende, R., Sequeira, P., & Sarmento, H. (2016). Coaching and coach education in Portugal. International Sport Coaching Journal, 3(2), 178-183.

Spanish Government. (1994). Real Decreto 594/1994, de 8 de abril, sobreense ̃nanzas y títulos de los técnicos deportivos. Boletín Oficial deEstado, 102, 13302–13308.

Spanish Government. (1998). Real Decreto 1913/1997, de 19 de diciem-bre, por el que se configuran como ense ̃nanzas de régimen especial lasconducentes a la obtenci ́on de titulaciones de técnicos deportivos se aprueban las directrices generales de los títulos y de las corre-spondientes ense ̃nanzas mínimas. Boletín Oficial de Estado, 20,2327–2338.

Schulenkorf, N., & Frawley, S. (Eds.). (2016). Critical issues in global sport management. Taylor & Francis.

Taylor, W. G., & Garratt, D. (2013). Coaching and professionalization. In Routledge handbook of sports coaching (pp. 27-39). Routledge.

Trudel, P., Gilbert, W., & Werthner, P. (2010). Coach education effectiveness. In J. Lyle & C. Cushion (Eds.), Sports coaching (pp. 135–152). London: Elsevier.

Trudel, P., Culver, D., & Werthner, P. (2013). Looking at coach development from the coach-learner's perspective: Considerations for coach development administrators. In Routledge handbook of sports coaching (pp. 375-387). Routledge.

Trudel, P., Milestetd, M., & Culver, D. M. (2020). What the empirical studies on sport coach education programs in higher education have to reveal: A review. International Sport Coaching Journal, 7(1), 61-73.

Tshube, T., & Hanrahan, S. J. (2018). Coaching and coach education in Botswana. International sport coaching journal, 5(1), 79-83.

van Klooster, T., & Roemers, J. (2011). A competency-based coach education in the Netherlands. International Journal of Coaching Science, 5(1), 71-81. https://atfca.com.au/find-a-coach/coach-education/.

Voicu, A. V., Stănescu, R., & Voicu, B. I. (2021). Professional Responsibility Of Coaches. Discobolul-Physical Education, Sport & Kinetotherapy Journal, 60(3).

Wareham, Y., Burkett, B., Innes, P., & Lovell, G. P. (2018). Sport coaches’ education, training and professional development: The perceptions and preferences of coaches of elite athletes with disability in Australia. Sport in Society, 21(12), 2048-2067.

Wagner, S. A. (2013). The Ethics of Coaching Sports: Moral, Social, and Legal Issues. Journal of Intercollegiate Sport, 6(2), 247-249.